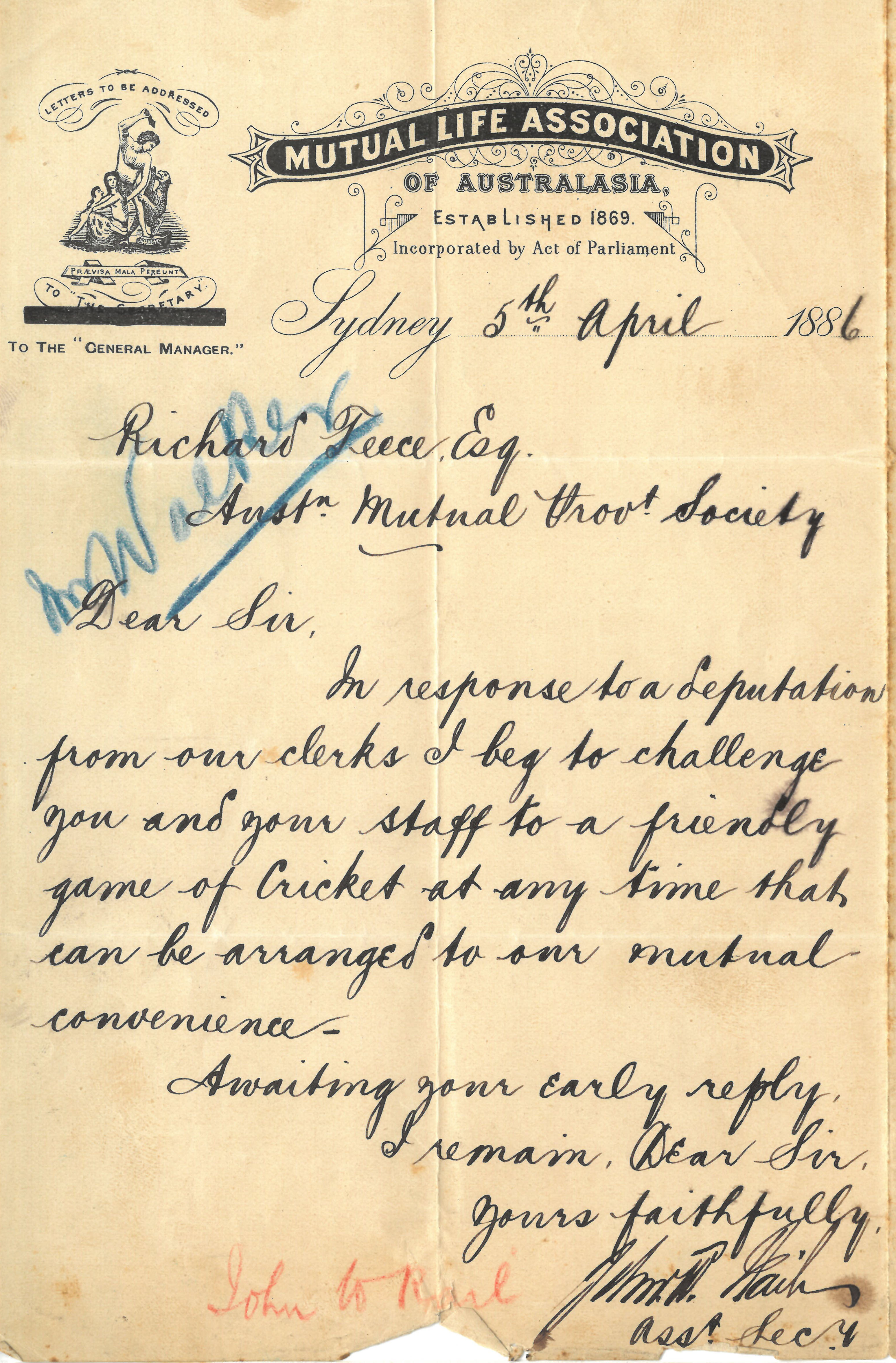

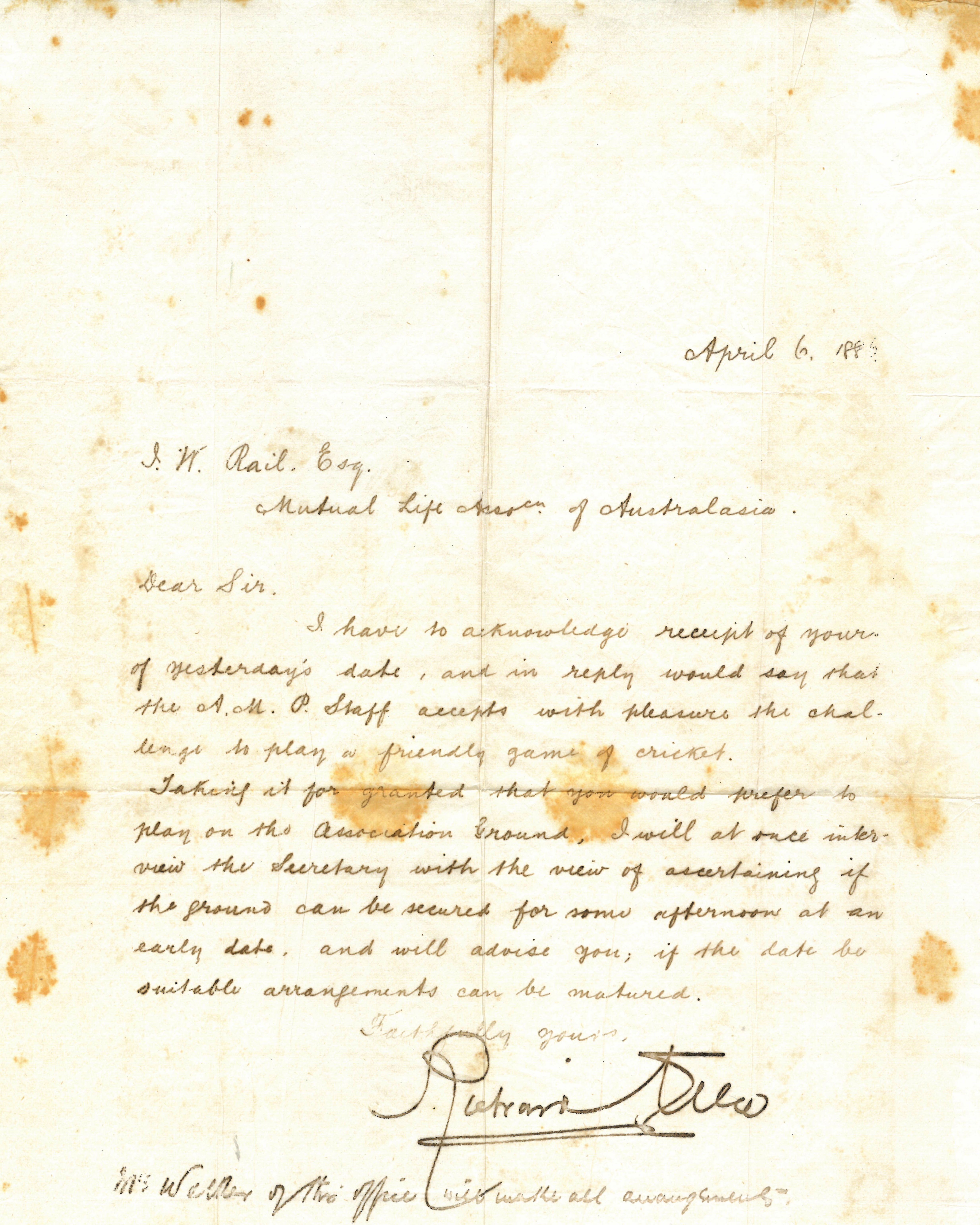

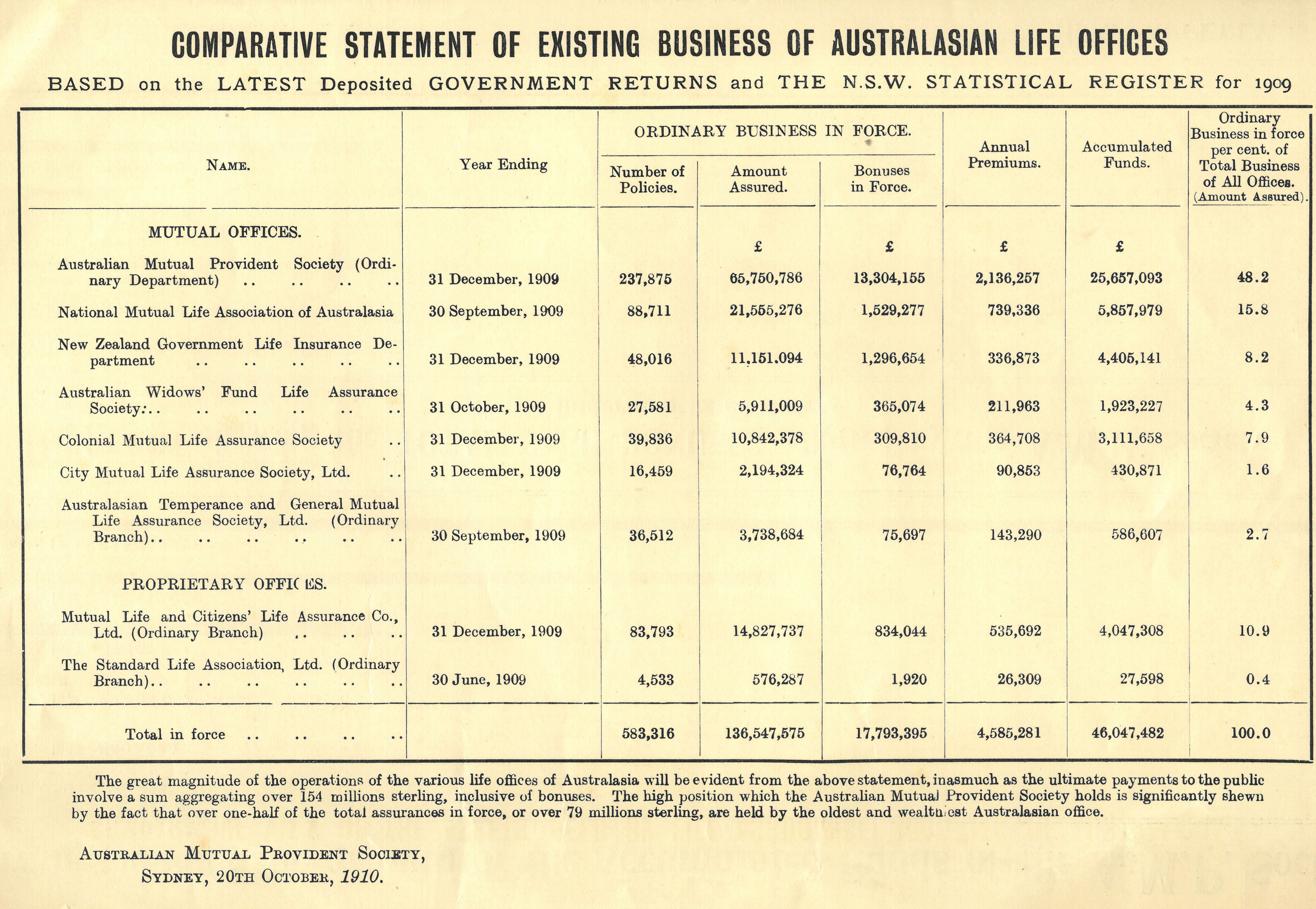

Although AMP was largely prudent and thoughtful in its business dealings, some of its early success must be attributed to the fact that it had very few rivals. This changed in July 1869, with the establishment of the Mutual Life Association of Australasia, which counted two former key AMP figures amongst its ranks, former secretary and actuary Robert Thomson and former consulting actuary Morris Pell, both of whom knew AMP’s business well. Within a month the National Mutual Life Association of Australasia also opened in Melbourne, promoting themselves as ‘locals’ rather than Sydneysiders like AMP. An explosion of Victorian-based rivals opened throughout the 1870s. By the end of the decade, Victoria was home to the Mutual Assurance Society of Victoria, the Australian Widows Fund, the Colonial Mutual Life Assurance Society, the Emerald Hill and Sandridge Mutual Provident Society, the Australasian Temperance and General Mutual Life Assurance Society, and the City Mutual Life Assurance Society.

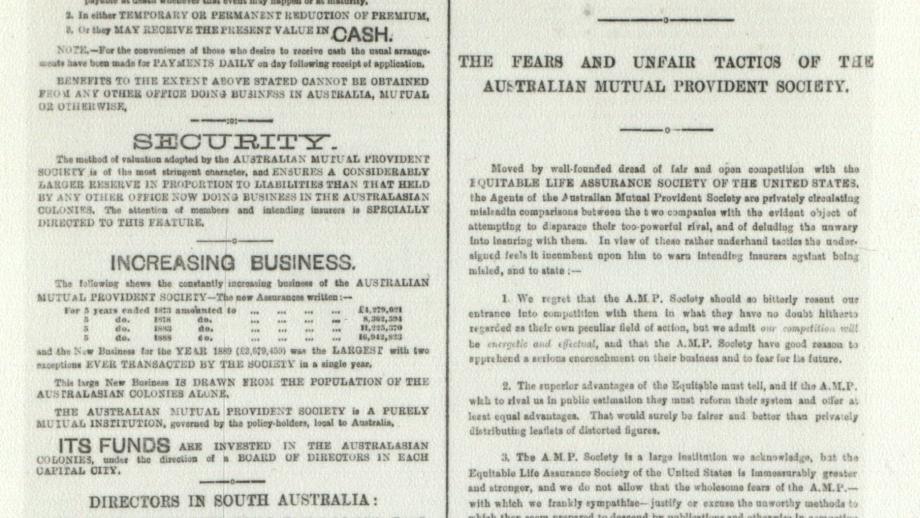

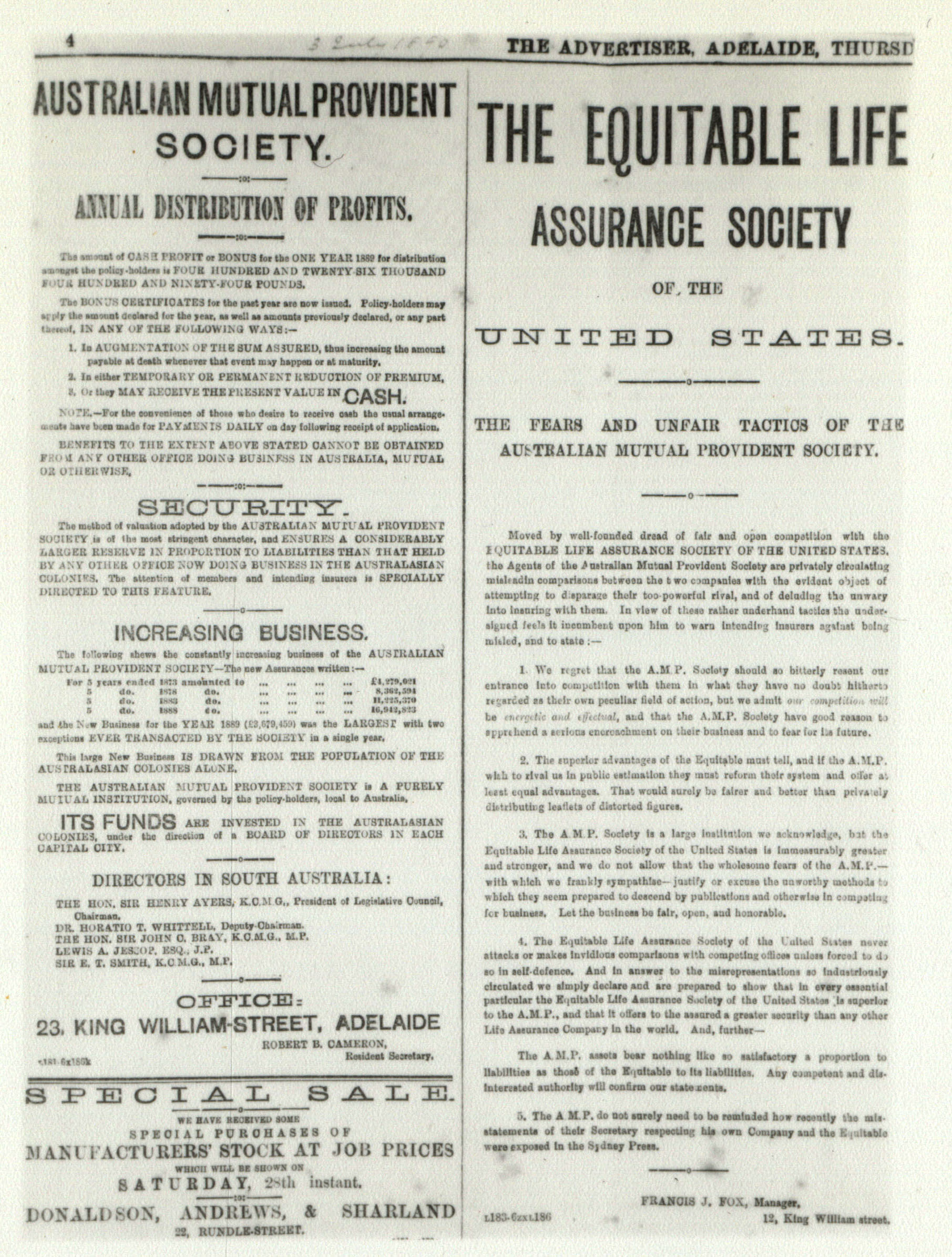

The late 1800s brought even more competition, particularly from new local branches of large American life assurance companies such as the Equitable Life Assurance Society of the United States and New York Life. An intense rivalry developed between AMP and Equitable Life, with AMP’s Richard Teece trading barbs in the press with Equitable Life’s C. Godfrey Knight. Equitable Life was larger, but AMP ran a much more efficient operation.

The American firms were not only selling the same life policies offered by AMP, but a new form of insurance known as the ‘tontine’. The tontine was “a mixture of lottery and life insurance” with members paying annually into a tontine syndicate, receiving an annual interest payment in return, and then as each member of the syndicate died, a greater share of interest would be paid to those remaining until finally the last surviving member of the syndicate would receive an amount more than 200 times what they had paid in premiums (Blainey, 1999). While the Americans and some Australian firms sold tontine policies, AMP refused to offer this product, with actuary Morrice Black labelling tontine policies as immoral and an incitement to murder (Blainey, 1999).

To combat increasing competition, AMP was forced to make changes to match and outdo its competitors. This included the introduction of a clause which protected policies from forfeiture if the early premiums had been paid and the option to pay annual premiums in small installments (Blainey, 1999). AMP and its rivals became much more aggressive in their sales tactics and paid additional fees to attract travelling salesmen and canvassers, and even lawyers and clergymen, who would make good commissions selling their products out in the suburbs and regions. AMP invested heavily in canvassers and agents, and these men became some of the best paid in Australia. In 1885, 83% of AMP’s business was brought in by its canvassers, who were paid 25 shillings for every £100 of business they created, or even more for those working in rural areas who incurred large travel expenses or top canvassers who were constantly being head hunted by rival firms (Blainey, 1999).

A side effect of all these new players was a growing popularity and understanding of life insurance and its importance. This benefitted both AMP and its rivals, with new business exploding. Perhaps the main casualty was the British life offices, who found that Australian customers were abandoning them, filled with a sense of nationalism and keen to give their business to local Australian offices.