Decentralisation and The End of an Era

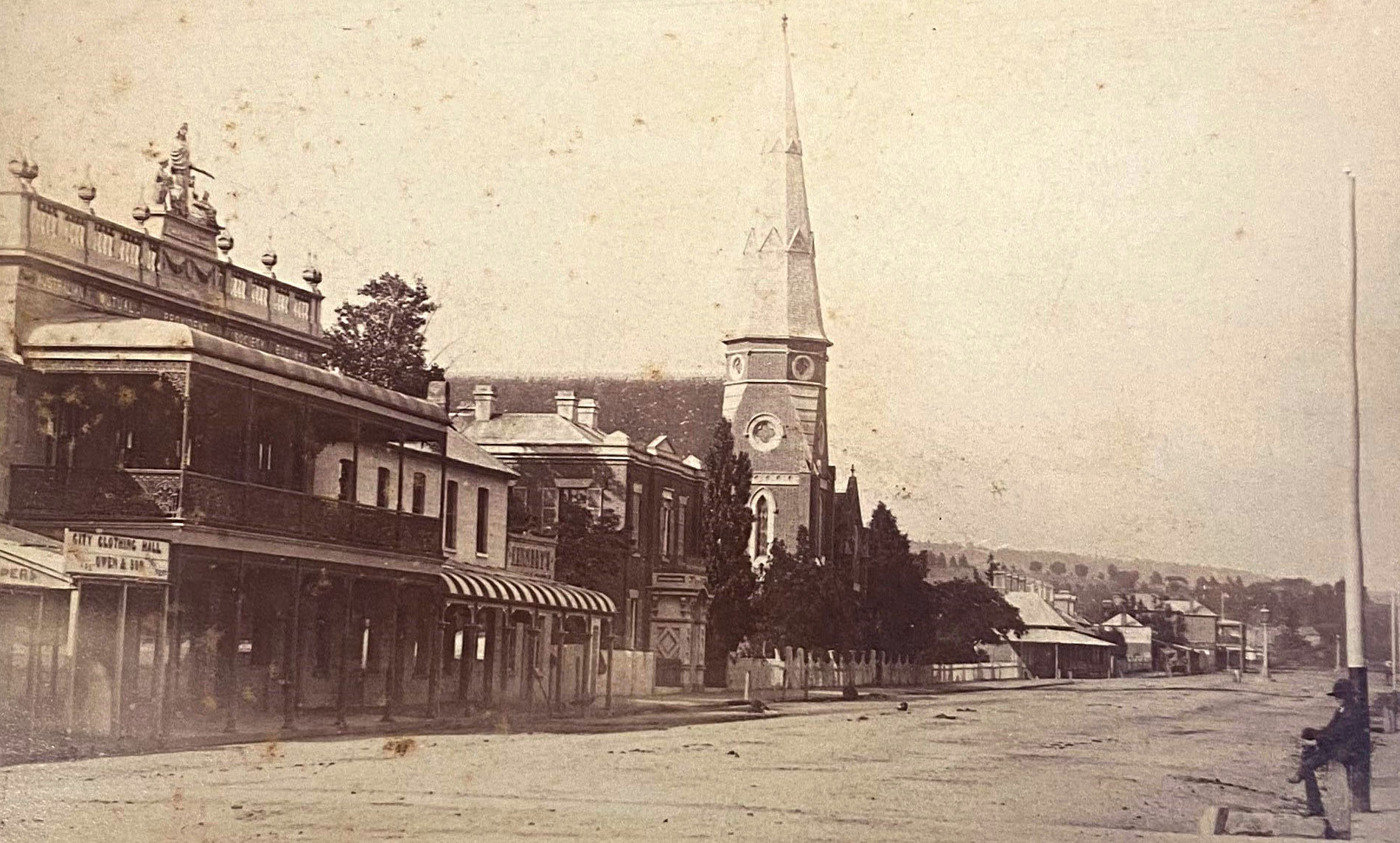

By the late 1800s AMP was acutely aware of the need to decentralise operations from Sydney and establish more local offices with local boards. New offices opened in Wellington (1871), Adelaide (1872), Brisbane (1875), Hobart (1877), Sydney (1880), and Perth (1884). The Sydney expansion resulted from the construction of a grand new building at 87 Pitt Street which opened on 1 July 1880. Designed by Mansfield Brothers of Sydney, the three-storey Renaissance style building was crafted from Sydney sandstone and featured Scottish granite columns, gold door handles, marble floors, and a spacious hall (Blainey, 1999).

The establishment of a local board and head office in Wellington, New Zealand, was important in shoring up business across the Tasman, which was under threat by the newly established Government Life Insurance Office. A temporary AMP office opened in Wellington in 1871. The local board met an astonishing 53 times in its first year and considered approximately 25-30 proposals at each meeting (Blainey, 1999). By 1877 a new office was opened in Wellington, employing twelve staff. This was followed by offices in Auckland, Christchurch, Dunedin, Oamaru, and Invercargill.

During the 1870s and 1880s AMP made many significant changes including the establishment of its first district offices under the leadership of district secretaries. Full-time canvassing agents were appointed, and they used the new district offices for advice and support.

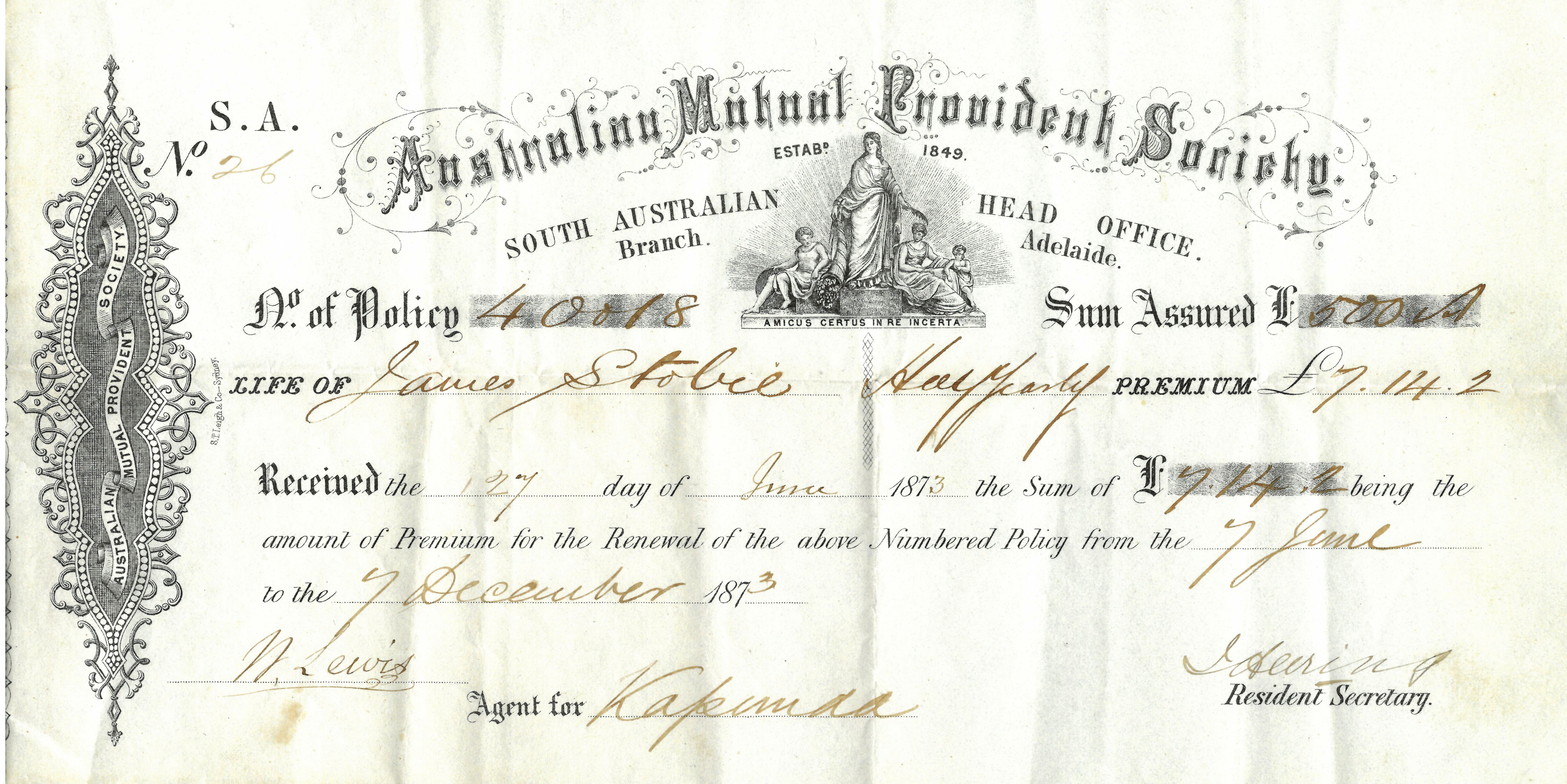

Up until 1870, life offices charged extra premiums for those in certain occupations including police officers, sailors, bakers, millers, and miners. This was discontinued, along with the practice of charging higher premiums for those living in certain areas, particularly those living in Queensland and ‘the tropics’, which had been controversial with AMP’s Queensland Board and risked sending potential policyholders to AMP’s rivals. After 1873 AMP allowed policyholders to reside in any part of Australia without paying extra premiums.

When the foundation stone was laid for AMP’s impressive new head office in Sydney in 1877, the growth of the Society could hardly be understated. By this time AMP was more successful than any other life office in Australia or Britain in signing up new business, and only three of the 76 life offices in Britain had more policies on their books than AMP (Blainey, 1999).

Despite this, AMP was underperforming in New South Wales bar for a few bright spots such as Goulburn, Grafton and Wollongong. To improve business, AMP divided the state into nine districts, with each supported by a district office, headed by a district secretary. The districts were: Sydney (supported by Head Office), Southern Sydney & South Coast (supported by Wollongong), North Coast (supported by Grafton), New England (supported by Armidale), Hunter River (supported by both Newcastle and Maitland), Western New South Wales (supported by Bathurst), Southern New South Wales (supported by Goulburn), Riverina (supported by Albury) and Northwestern New South Wales. This decentralised model became so popular that it was soon replicated across the other Australian states and New Zealand.

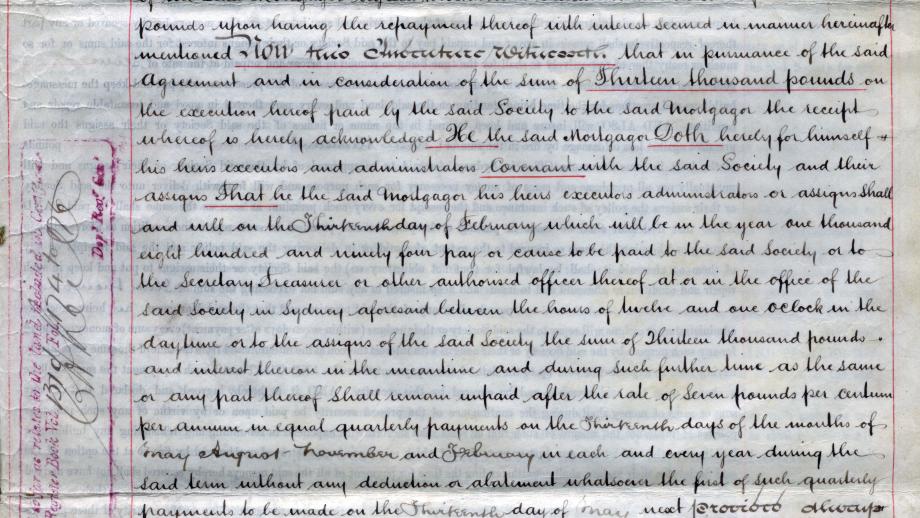

In 1884 the Society achieved a result that no other life office in the world had been able to achieve, a distribution of £1,000,000 to its members. Actuary Morrice Black wrote of the Society…

“The small beginnings of an unpretending friendly society established without capital or assistance of any kind from its promoters, except their gratuitous services in its management, are in striking contrast with what it has now become – the greatest and wealthiest monetary institution in Australia”.

Amidst the increasing competition of the 1880s, AMP actuary Morrice Black made a rare error when he insisted caps be placed on canvassers’ commissions. Subsequently, rival firms poached some of AMP’s best staff. To combat this, Black pitched an innovative new incentive to help retain and attract staff, an AMP staff superannuation scheme.The new AMP staff superannuation scheme essentially offered social security to AMP employees, many of whom curiously did not hold AMP life assurance policies. The scheme, known as the Scheme of Assisted Assurance and Superannuation Allowances, was approved in 1885. Eligible staff would pay for a policy insuring their life for an amount equal to at least one year’s salary. This was known as a member’s policy. An additional policy, known as an official policy, would also provide insurance for a similar amount, with this policy paid for by AMP. However, there were broad objections to the scheme’s generosity and its cost to AMP’s policyholders, so in 1888 a new scheme was devised, known as the Officers’ Provident Fund. AMP contributed £25,000 to this new fund, with each employee contributing 2.5% of their monthly salary.

The Officers’ Provident Fund would pay a pension to employees aged over 60 who had worked for AMP for more than 20 years. In this sense, the fund aided older long-term employees, rather than the younger canvassers that were being enticed by rival firms, so while it was an innovative idea, it did not produce the desired outcome and AMP continued to lose agents and business, particularly to its American rival Equitable Life.

For many years AMP was overseen by the managerial duo of secretary Alexander Ralston and actuary Morrice Black. Ralston and Black had very different styles. Ralston was a competent, patient and careful negotiator who “guarded the fort” while Black was more of an innovator and troubleshooter (Blainey, 1999). Both were highly respected and integral to AMP’s success, but during the 1880s both were plagued by health issues. Ralston was advised to take nine months leave for his health in 1884, but despite this break, upon his return he was unable to cope with his previous workload and he was subsequently directed to retire, even though he was aged only 53.

After Ralston’s retirement, many of his duties fell to Morrice Black, who also continued his duties as actuary. In 1887, Black’s wife, who had earlier relocated to Britain with their children so they could continue their studies, returned to Sydney, with the couple residing at their grand home ‘Tivoli’ in Rose Bay which had been designed for Black by renowned architect John Horbury Hunt. However, it was around this time that Black’s health also began to fail. In 1889 Black took extended leave to focus on his health, but upon his return he was diagnosed with Bright’s Disease (an inflammatory kidney disease now known as acute glomerular nephritis), and this forced him to reluctantly retire at the age of 60. He died shortly afterwards, on 27 August 1890. Alexander Ralston, with whom Black had worked so closely, had died the previous year on 2 May 1889 at the age of just 56.