Challenging Times and the End of the Port Stephens Estate

The 1840s presented many challenges not only for the Company, but for the Colony. Drought and economic depression significantly impacted the Company, particularly at Warrah, with the drought on the Liverpool Plains being most severe. The Company was forced to boil down sheep for tallow; the price for cattle collapsed; the demand for coal fell away; staff wages were reduced; and the Company was struggling with its mining workforce at Newcastle.

To raise some capital, the Company sought the freehold title for its estates, with a view to selling off some of its land. Under the original terms of its arrangement, the Company would receive its land title when it had relieved the Colonial Treasury of £100,000, by maintaining convicts and making improvements to its estates. By 1844, the Company reported it had spent £131,000 on convicts and £80,000 on improvements. However, the Company entered protracted negotiations with the Colonial Government in 1838 and it was not until the mid-1840s that the Government finally concluded the matter would be resolved by an Act of Parliament. Under considerable pressure, the Company agreed to end its 31-year coal monopoly. On 7 August 1846 the Act received Royal Assent and a Royal Warrant was issued authorising the conveyance of all the Company’s land. A Deed of Grant was issued in November 1847. This would allow the Company to sell some of its land holdings and raise much-needed capital.

This coincided with the Company seriously considering its future in the Colony. With low wool prices, ongoing labour shortages and drought, and the unsuitability of some of its land for keeping sheep, it was clear the Company would struggle without significant changes.

In the late 1840s the Company decided to promote a colonisation scheme to revive its fortunes at Port Stephens, with a pamphlet titled Emigration to Australia created and distributed in England. The Company’s proposal was the following…

“Farms and vineyards which have long been in cultivation, with excellent homesteads attached, will be offered for sale at twenty years purchase on the estimated annual value. The uncultivated land will be sold in lots of 50 acres and upwards at £1 per acre; each £50 paid in England entitling the purchaser to a choice, and free passage in one of the Company’s ships to Port Stephens. Each lot to include pasturage for stock on adjoining land at a low poll tax. The Company is willing to lease land for ten years, with the right to purchase at £1 per acre in that term”.

Despite lowering the initial minimum purchase from 200 acres and spreading the payments out over time, the level of interest in the scheme was low, with only 15 certificates issued from 90 enquiries (Pemberton 2011).

Of the immigrants that arrived in Port Stephens, the general opinion of them was poor. General Superintendent Archibald Blane wrote in June 1851…

“They have all seated themselves down in some patch of rich bush land, thickly timbered, wholly unsuited for agricultural purposes, and, with the exception of three, have neither the energy, skill nor capital; and in some instances have sold the whole of their allotments, and all are fast degenerating into a state of poverty and wretchedness”.

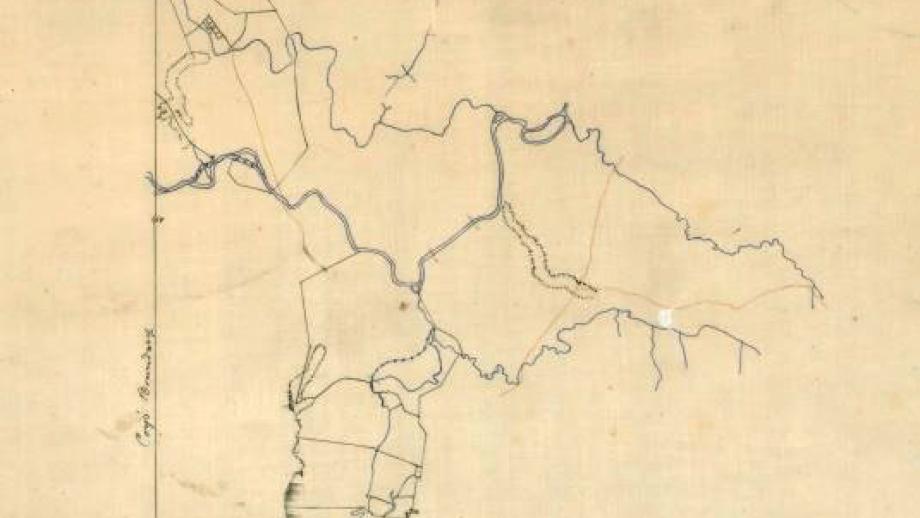

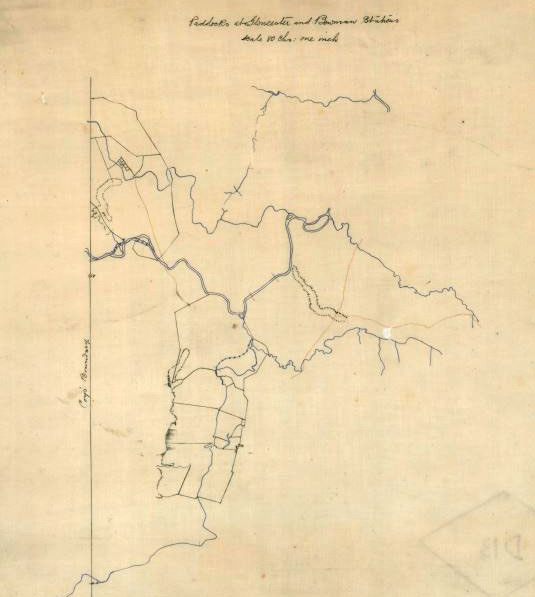

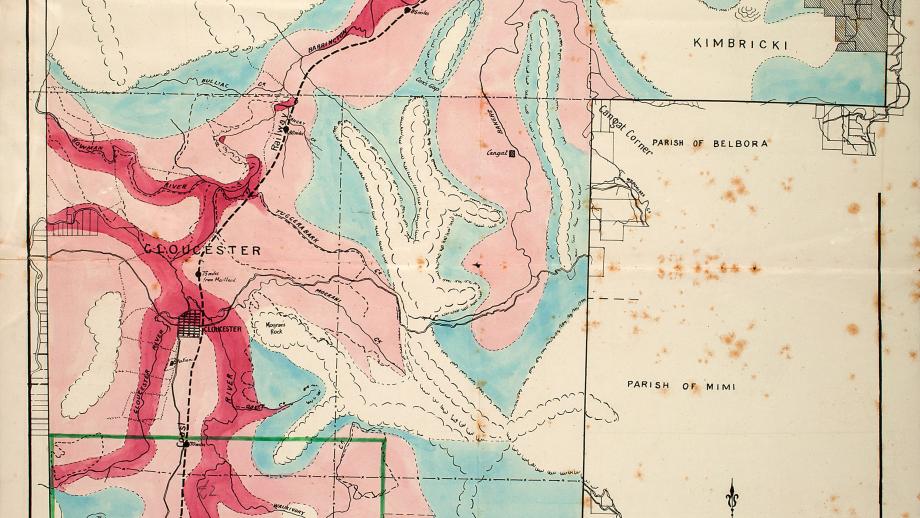

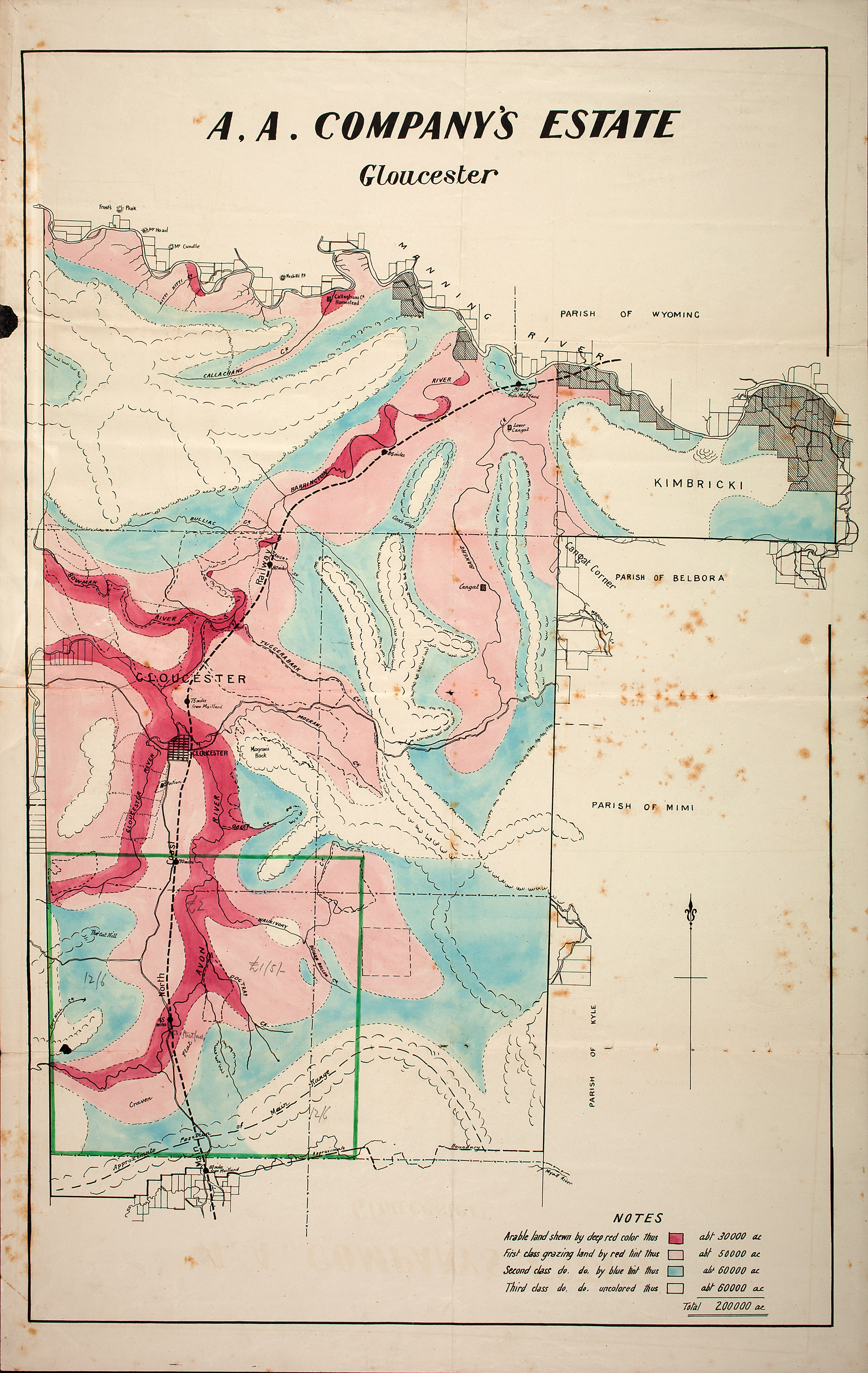

By early 1856 the Company had decided to move the last of its sheep to its Warrah and Peel Estates and disband its establishment at Stroud on the Port Stephens Estate. The focus at the Port Stephens Estate would now be on cattle at farms at Gloucester and Bowman River in the north, with land around Carrington, Stroud, and Gloucester to be sold off, some as 50-acre farm lots. From the 1860s the Company also offered leases on large areas to be used as cattle runs.

In attempts to make Port Stephens more attractive to settlers, the Company encouraged trials of crops including cotton, vines, tobacco and even silkworms, but none of these ventures met with much success. There were also hopes to develop mineral resources on the Estate, but this amounted to nothing.

Small lots on the Karuah and Myall Rivers and northern shores of Port Stephens were leased or sold to timber getters and in the 1870s the Company’s directors reluctantly agreed to ringbark much of the Estate to improve the pastures. Tahlee House, Booral House, Stroud House, and Telligherry Cottage were all sold or leased.

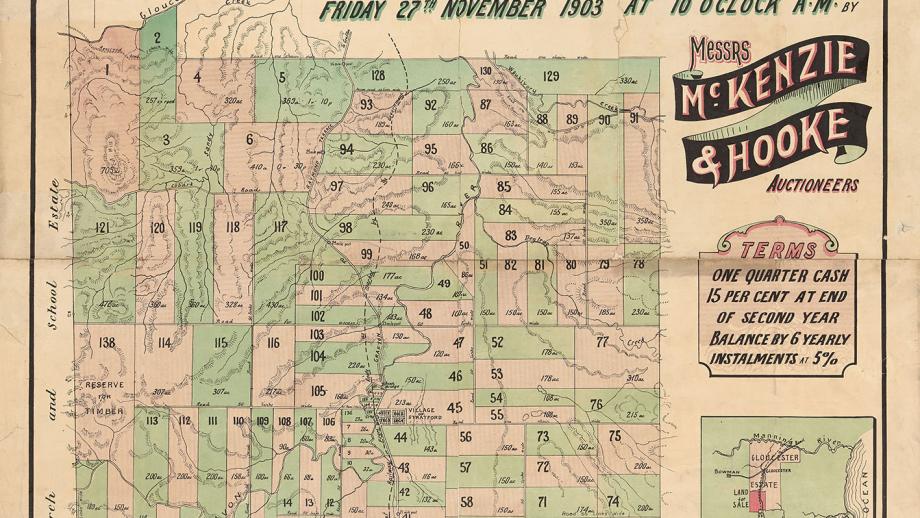

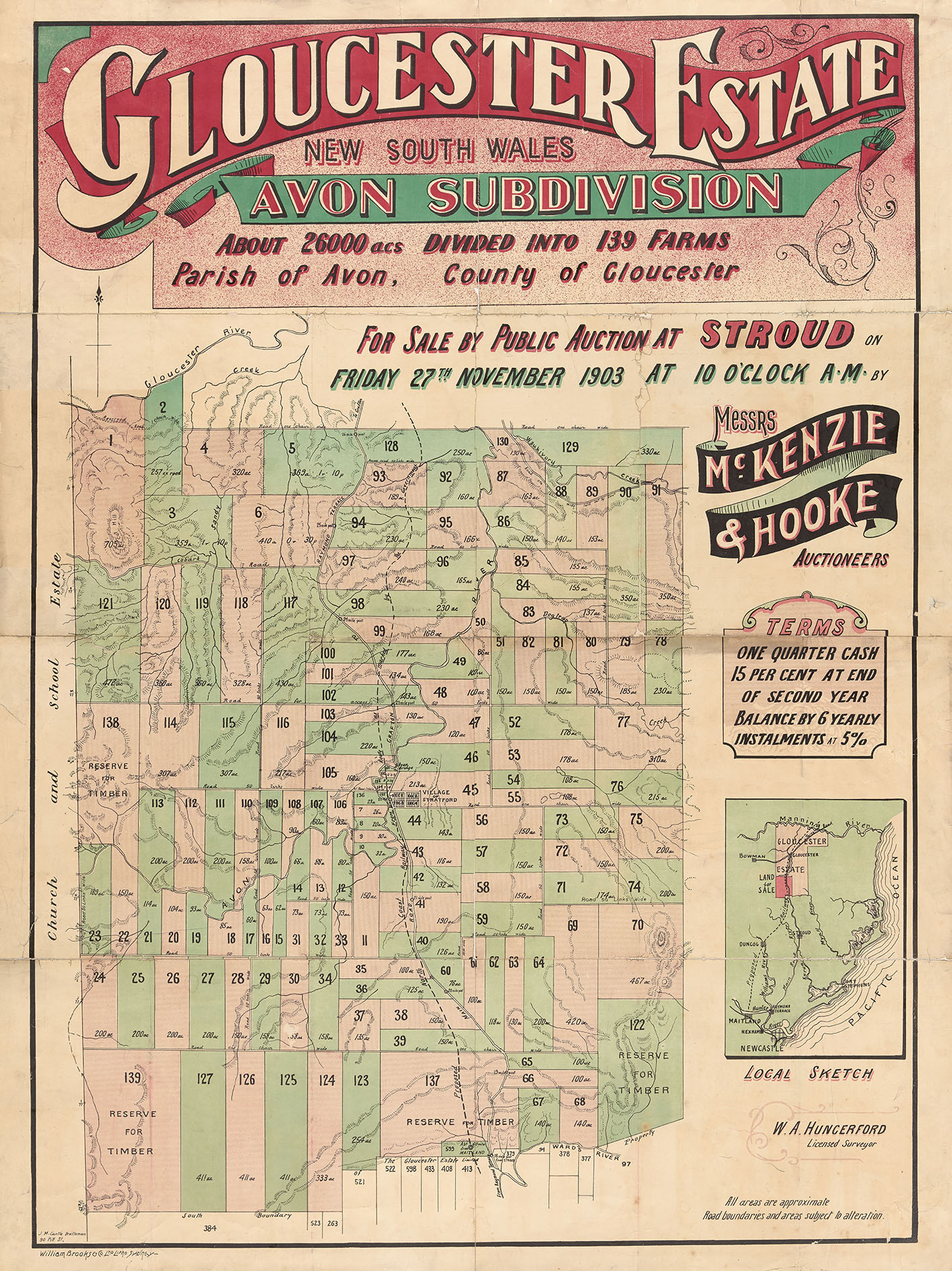

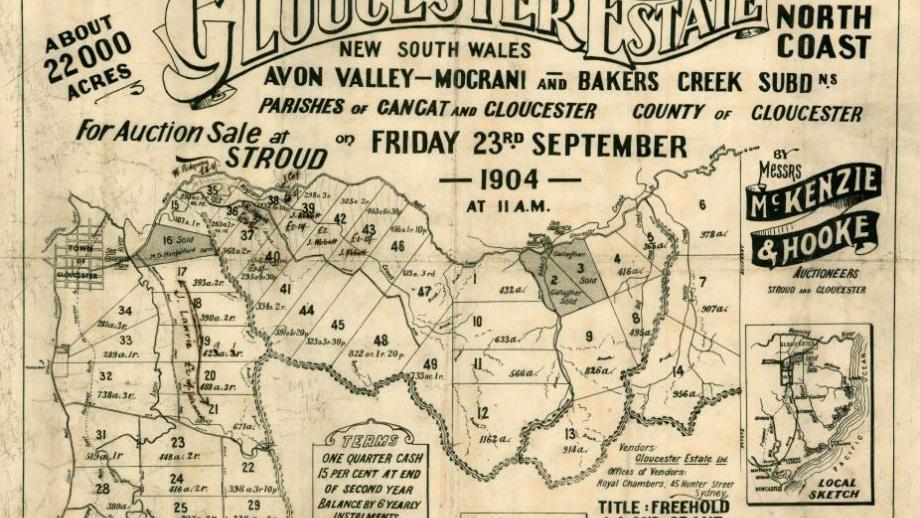

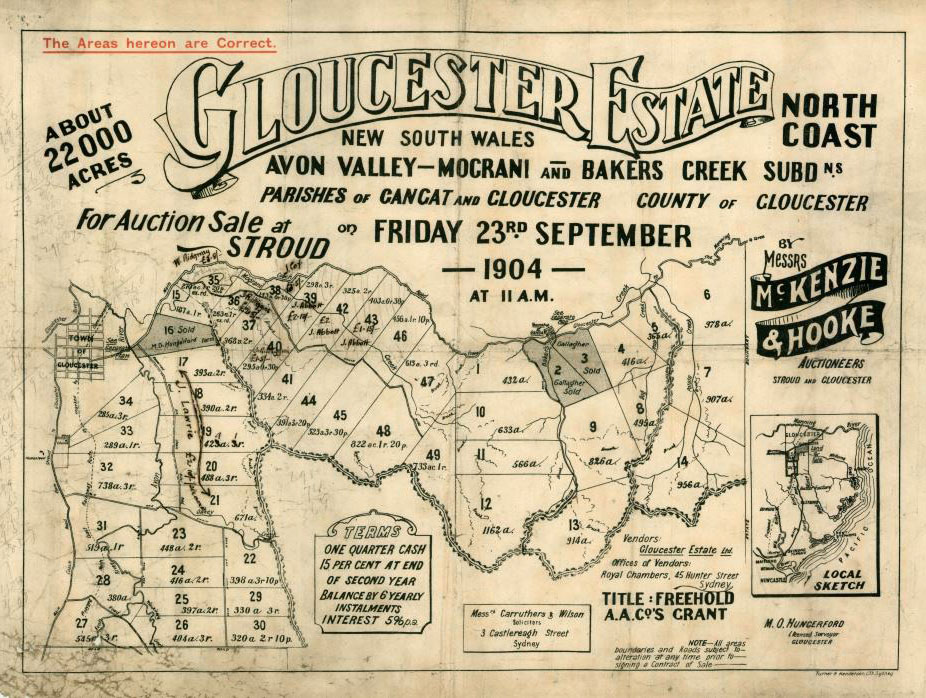

The reality was that despite spending hundreds of pounds developing a road between Gloucester and New England, Port Stephens remained out of the way. Facing increasing land taxes, the Company sought to offload the last of its Estate. All remaining land there was offered at 10/- an acre, but with no result. Consequently, in 1902 the Gloucester Estate Syndicate purchased 200,000 acres north of Stratford for subdivision, mostly as dairy farms. The Syndicate also purchased the Company’s remaining cattle there at £5 per head.

By the 1920s, only a few acres of the Company’s land remained at Port Stephens, and the focus firmly shifted to its estates at Warrah and The Peel.

References

Pemberton, P 2011, Pure Merinos and Others: The Shipping Lists of the Australian Agricultural Company, ANU Archives of Business and Labour, Canberra.