Coal

During Sir William Parry’s time as Commissioner the Australian Agricultural Company took over the government’s coal mining operations in Newcastle, New South Wales. This venture had initially been explored before Chief Agent Robert Dawson had even left England for Australia in 1825, with the Company’s Court of Directors forming a Coal Establishment under the approval of the Colonial Office.

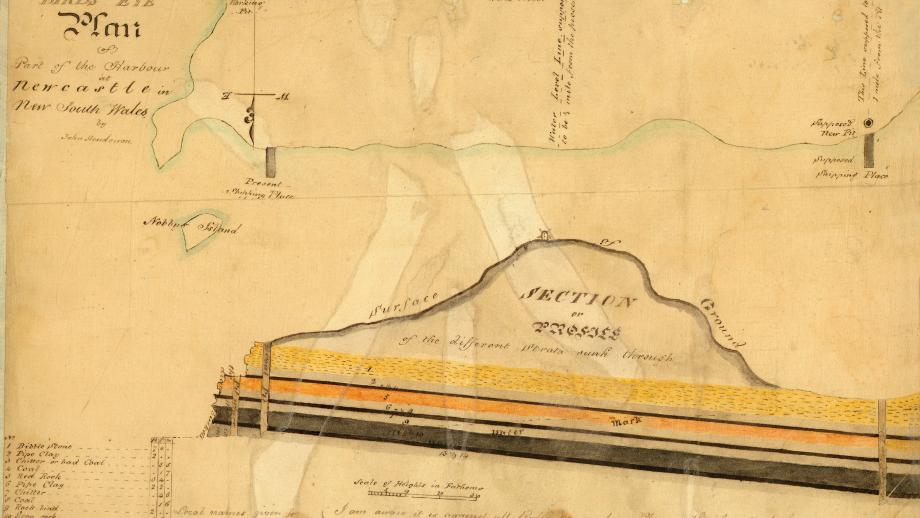

In July 1826, a party led by John Henderson, sailed to New South Wales to investigate the prospects of coal mining. The proposal was poorly received by Governor Sir Ralph Darling and the Company’s Colonial Committee. After all, this was a very different venture to raising sheep. Although survey work was completed at Newcastle and Parramatta, the Colonial Committee dissolved the Coal Establishment, and nothing came of the proposal until 1828 when the Colonial Office granted 2,000 acres at Newcastle to the Company along with the right to mine coal there. The agreement stated that the New South Wales Governor could not grant any further coal rights or assign convicts for the working of any other coal for the next 31 years, and in exchange the Company would supply the government’s coal needs at prime cost to one quarter of the year’s output and those of the public at reasonable prices (Pemberton 2011). This provided the Company with a much resented 31-year ‘monopoly’ which was intended to compensate it for its earlier abortive expenditure.

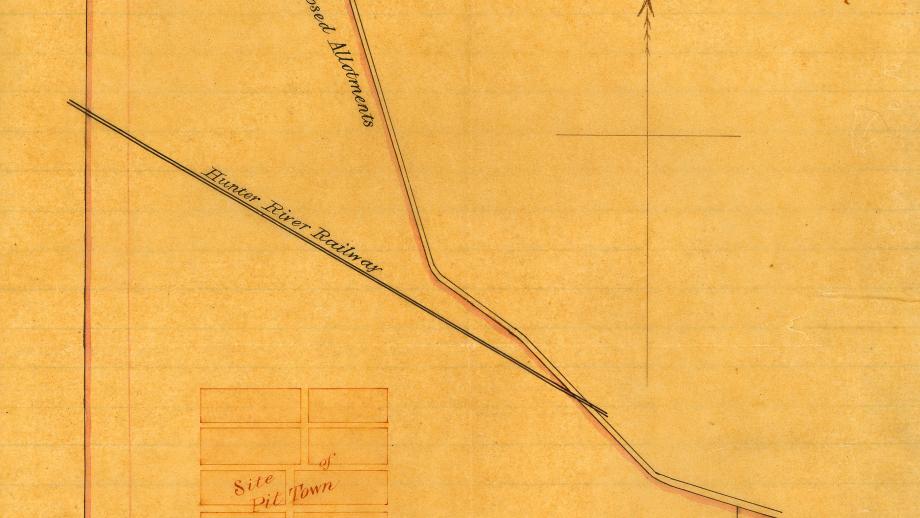

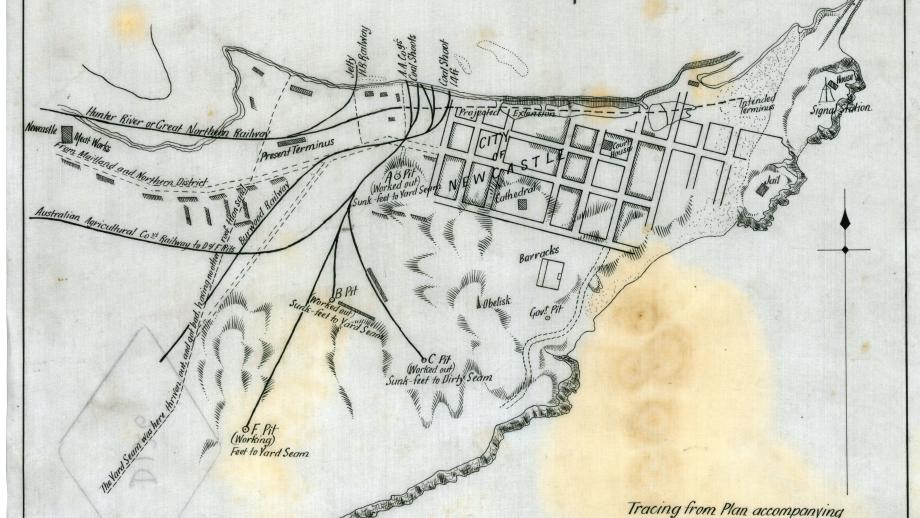

After surveying the government coal works, John Henderson decided the Company should choose a new site for their first pit, which would be known as the A Pit. It was located near what is now the corner of King and Darby Streets in Newcastle. The A Pit, a horse railway, and wharf were officially opened on 10 December 1831.

The coal operations initially proved lucrative, with an output of 5,000 tons in 1831 growing to 30,500 tons in 1840. Much of this growth was due to the increasing use of steamers to transport goods and greater domestic demand as wood became more difficult to obtain in Sydney. Export markets to South East Asia and South America also increased demand. To meet this increasing demand, the Company sunk two new pits: Pit B located just south of Pit A (1837) and Pit C located south of Pit B (1842).

In 1838, the Company bought 2,000 acres to the west of Newcastle at Platt’s Estate. Mr J.L. Platt had been working coal there before the Company commenced operations, and upon his death, they seized the opportunity to purchase his land from his son and work the area themselves. The Company had to wait until Platt’s son turned 21 and was legally able to sell the land. In August 1838, the Company paid him £6,000 and secured the purchase.

By the mid-1840s the Company was experiencing a variety of problems with its operations at all its pits. The reserves at A Pit had been exhausted, shifting sands were proving problematic at B Pit, ventilation was poor at C Pit, and the Platt’s Estate was not as fruitful as had been hoped. In response, the Company put down the D Pit to the Borehole Seam in the western part of the Newcastle Estate, and this became the centre of mining operations for the next 20 years.

In Newcastle the Company constructed offices and timber yards. Near the B Pit, the Company constructed houses for its ‘free’ workers, with its convict workers housed in government barracks in Newcastle.

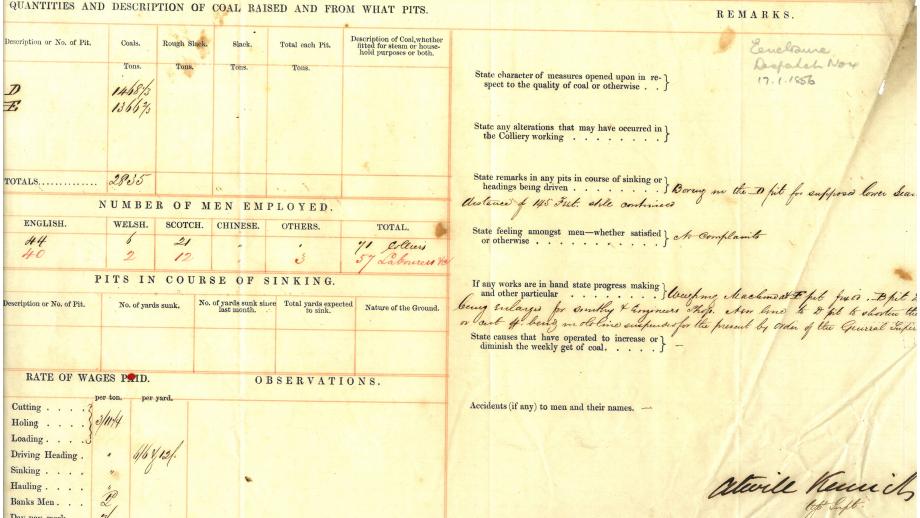

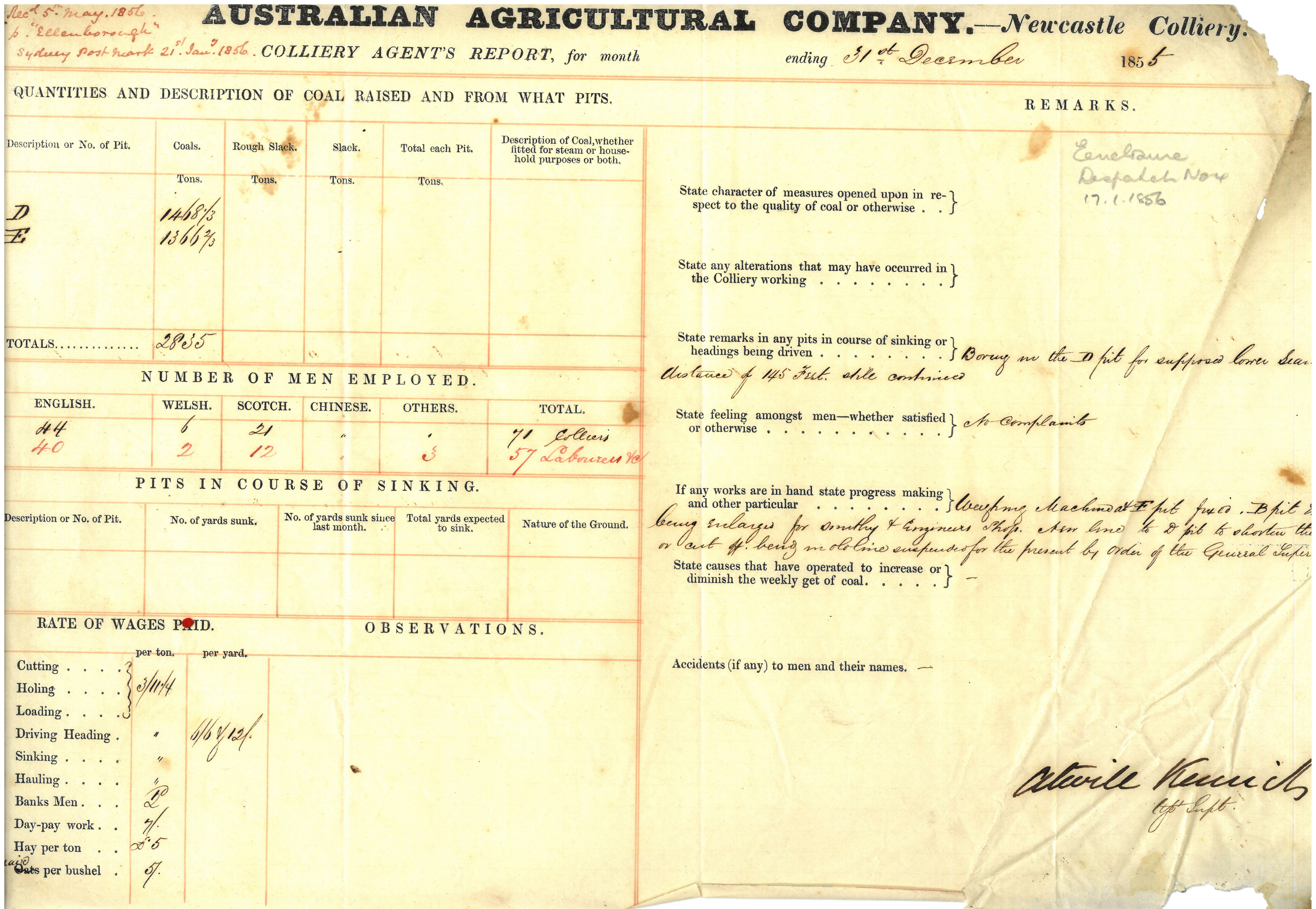

The Company encountered some difficulties with its workforce in Newcastle. Many of the convicts assigned to them had come from chain gangs and were difficult to control. The recruitment of miners from Britain proved mixed. Upon arrival in Sydney, some had immediately found work that was more lucrative and consequently failed to take up work for the Company in Newcastle. However, the Company successfully recruited a number of miners and blacksmiths, particularly from Scotland.

In the 1840s, the Company’s coal monopoly came under increasing pressure and amid a colonial investigation into the New South Wales coal industry, the Company reported it had been operating its mines at a loss for five years and struggling with the cost of labour and falling coal prices due to competition and economic depression. In 1847, the Company agreed to abandon the protection of its monopoly and any claims for compensation under it.

Growing demand on the coalfields and an increasing demand for labour saw the Company regularly recruit more miners from Britain as well as advertising extensively throughout New South Wales and Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania). In 1850 almost all the Company’s miners struck for an advance in wages. Commissioner James Ebsworth’s response was to request the London-based Company directors to send out more miners and he suggested recruitment from different districts of England and Wales to break up local loyalties. The miners would be offered staggered contracts to prevent them leaving en masse during peak periods. The miners would also not be promised flour or housing, which were both difficult to obtain in Newcastle at the time. The miners’ contracts would be for a period of at least two years to allow time for them to repay their passage.

During the early 1850s complaints about poor administration at Newcastle reached the Company’s directors in London and it was clear there was a need for new management. A new Mine Agent, Frank Beaumont, and Wharf Agent, Alfred Butcher, were appointed and travelled to Newcastle from Wales in June 1853, along with more miners from South Wales and Cornwall. More strikes ensued when the miners arrived to find that horses were not used below ground. Both Beaumont and Butcher also objected to the accommodation offered. Within a year, both Beaumont and Butcher had been suspended and replaced by William Wood (in England) and James Corlette (in New South Wales) respectively. Wood quickly set about purchasing the machinery and equipment necessary to modernise operations, the most successful of which were two locomotives that replaced horse traction on the surface railways and were in use for 30 years (Pemberton 2011). When Wood declined to travel to Newcastle, he was replaced by Robert Whytte, however Whytte’s tenure was highly problematic, and he was dismissed in January 1860. By this time, the Company had established a new No 2 Pit east of the D and E Pits.

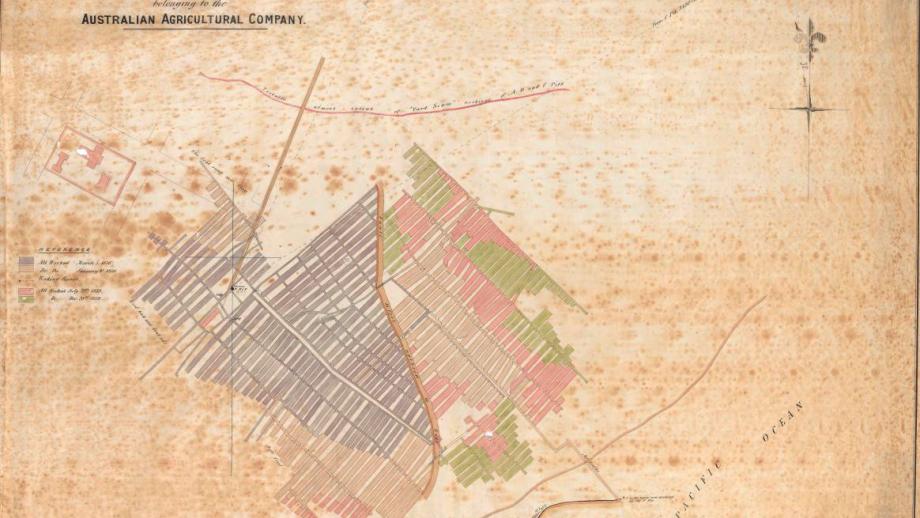

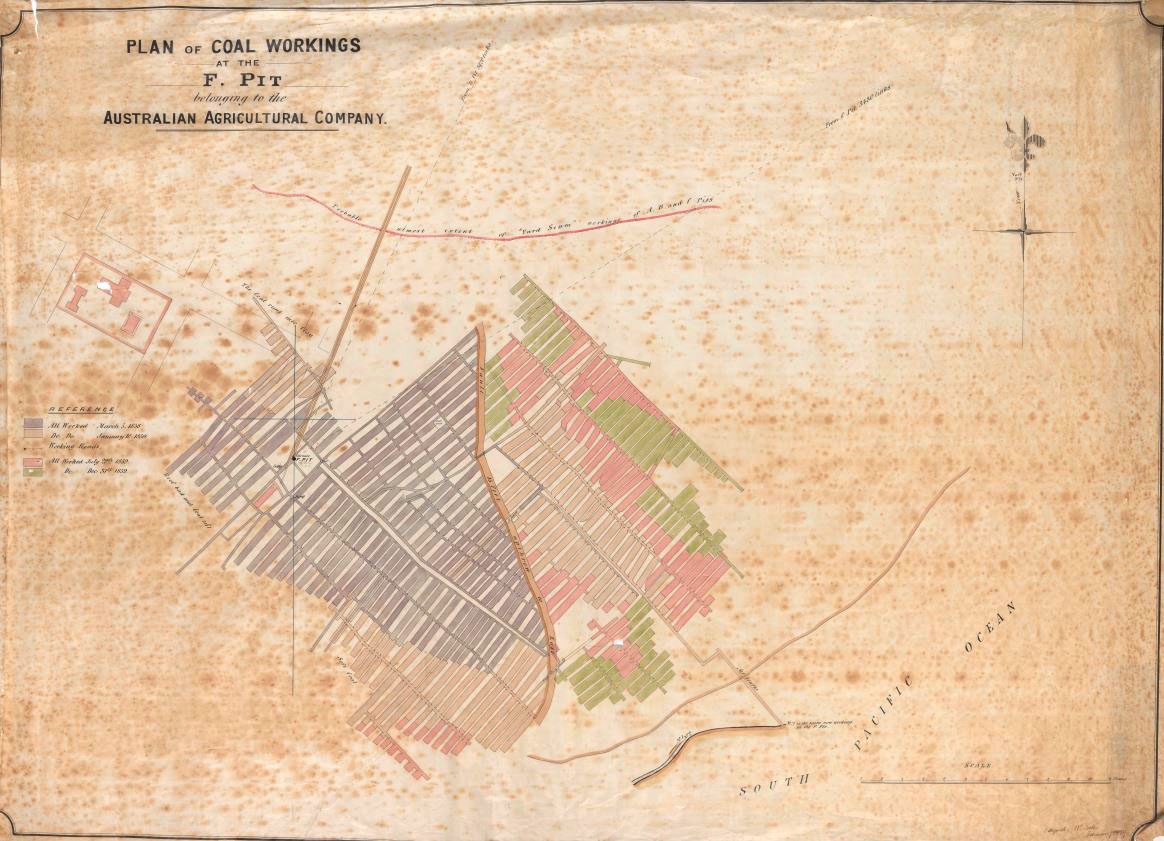

During the early 1860s, the Company’s mining operations, along with those of other colliery proprietors such as the Newcastle Coal and Copper Company, J&A Brown of Minmi, and the Tomago Company, were plagued by worker unrest and strikes. New miners were regularly recruited and transported from Britain, along with those from Victoria, Tasmania, and New Zealand, but problems persisted, and the Company resorted to evictions of miners who were tenants on its Newcastle Estate. The Company had opened an F Pit and No 2 Pit, but the former was closed during an 1862 strike and not re-opened. The D and E Pits closed in late 1863 and all work was concentrated at the No 2 Pit until the opening of the Hamilton Pit in 1874.

During the 1870s and 1880s the Company successfully worked the No 2 Pit and Hamilton Pit and leased 400 acres adjoining the Burwood Coalfield to extend their operations. However, on 22 June 1889 a roof fall killed 11 miners at the Hamilton Pit, and it was subsequently closed. The No 2 Pit continued to be operational until March 1901.

In 1884 the Company began boring south of the old C Pit, and the New Winning (Sea Pit) began working as a separate pit in November 1888. The coal was reported to be of the highest quality and seam of great thickness (Pemberton 2011).

By the turn of the century, the Company's Newcastle field was almost worked out and so in 1901 the Company purchased 1,280 acres at Hebblewhite, 30 miles west of Newcastle, along with a further 3,152 adjoining acres in 1902. Here they established the Hebburn Colliery in 1904 and additionally made a considerable investment in the Aberdare-Cessnock Railway. The company Hebburn Ltd was formed in 1914 to take over the running of both the colliery and the railway, with the Australian Agricultural Company being a major shareholder until 1949.

The last of the Company’s mining operations was the Sea Pit but this became increasingly difficult to work due to major subsidence and decreased output. When this pit was finally closed in October 1916, it marked the end of the Company’s interests in coal mining in New South Wales.