The Workers

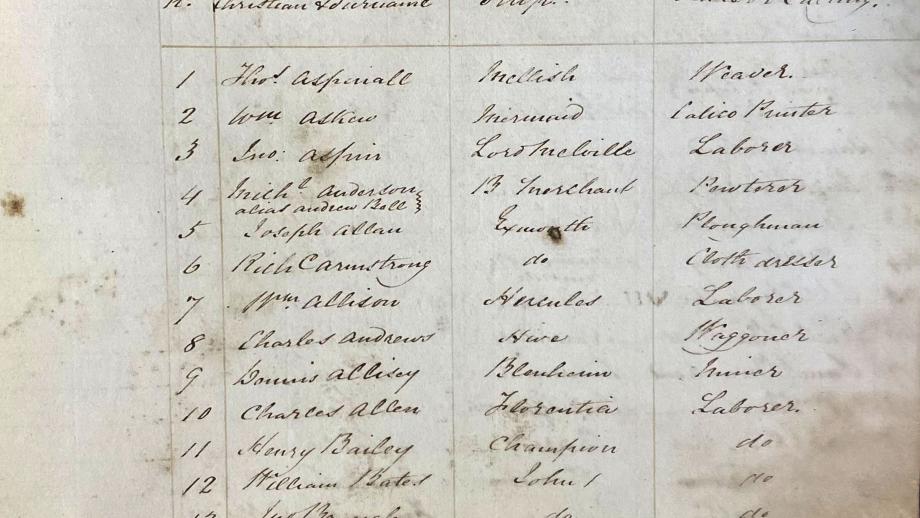

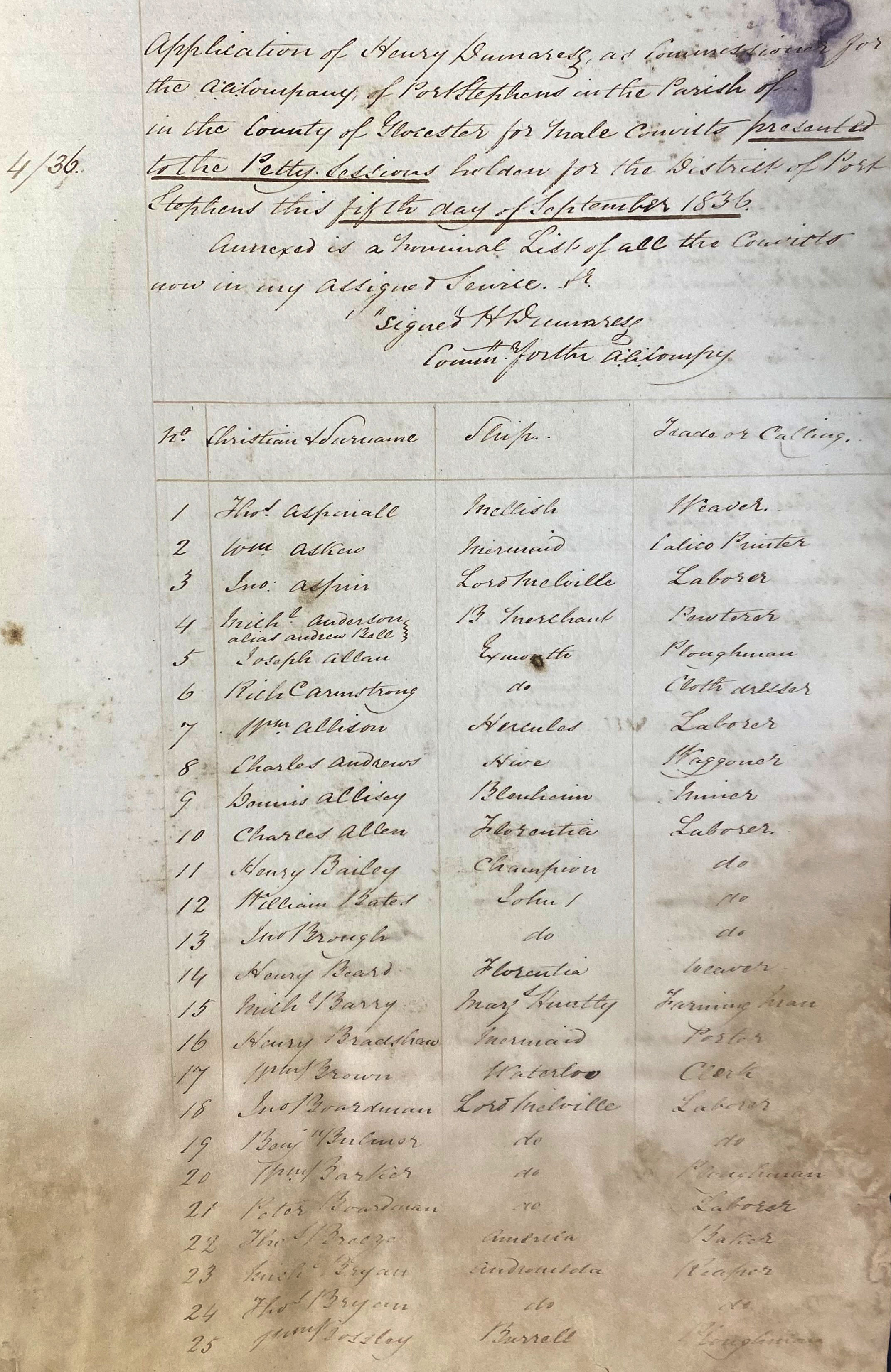

Initially most of the Company’s workforce comprised indentured workers from England and convicts sourced from the New South Wales Government. However, convicts were in much shorter supply than the Company had anticipated. It was noted in a despatch to the Company’s Governor on 2 March 1826 that “the procuring of a supply of government servants adequate to the demands of the Company will we fear be scarcely practicable. Giving to the very small numbers that have of late arrived, instead of a “surplus” there is so great a scarcity of prisoners, that Mr Dawson was unable to obtain any to accompany him to Port Stephens” (Australian Agricultural Company despatch book, 78-1-1).

Despatches throughout 1826 report a small supply of convicts assigned to the Company, with some praise from Chief Agent Robert Dawson for their overall behaviour. For those that didn’t comply, punishments were severe. A despatch written by Dawson in July 1826 lists the charges and sentences for convicts, as well as emancipated and free men. Examples include 50 lashes for “refusing to go to work” and “repeated neglect of duty”, two months imprisonment for “absenting themselves before completing their contract”, and three months imprisonment for “refusing to obey the superintendent’s orders and insolence” (Australian Agricultural Company despatch book, 78-1-1).

By 1828, the Company had managed to acquire 180 convicts to work at the Port Stephens Estate. However, the need for a larger workforce and those with specialist skills, prompted the need to recruit workers from other areas.

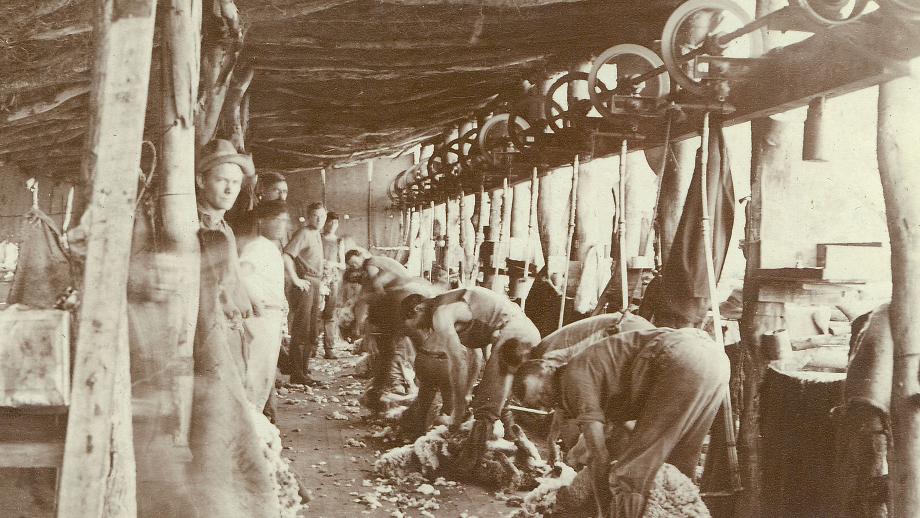

To tend to the Company’s flocks, large numbers of shepherds were required, and these were commonly recruited from England, Scotland, Ireland, and Germany. In 1838 Commissioner Phillip Parker King suggested the Company recruit unskilled labourers and train them as shepherds in Australia’s unique conditions rather than sending skilled English shepherds who would need to be retrained. A migration scheme was established, managed by an English emigration agent Mr Marshall and two Irish agents John Besnard Jnr and Mr Clendennin, with Marshall agreeing to obtain a hundred labourers at a commission of £5 per head and £3 for the Irish agents. The Irish recruits would be single men between the ages of 18 to 27. They would be given £5 for expenses, an advance of their passage money, and wages of £15 per year. Although some men failed to arrive from Ireland for the journey and others refused to embark, approximately 100 Irish labourers left Plymouth for Sydney in 1838. Upon arrival in Sydney, many complained about misinformation regarding promises of land and clothing. Some left Sydney immediately for more lucrative positions and others refused to make the journey to Port Stephens. For example, only four of the 31 Irishmen that arrived aboard the Mary Anne, made it to the Company’s Port Stephens Estate. Of the Irish workers that made it to Port Stephens, most absconded within 12 months and only few were considered capable of working as shepherds. In contrast, in 1841 the Company recruited 41 specialist shepherds from Devon in England. Commissioner King was generally happy with the Devonshire shepherds, who had travelled to the Peel Estate or Gloucester, although he noted that “the old colonial shepherds, freed or ticket of leave men, at one third less (in wages) take twice the care of double the number of sheep”.

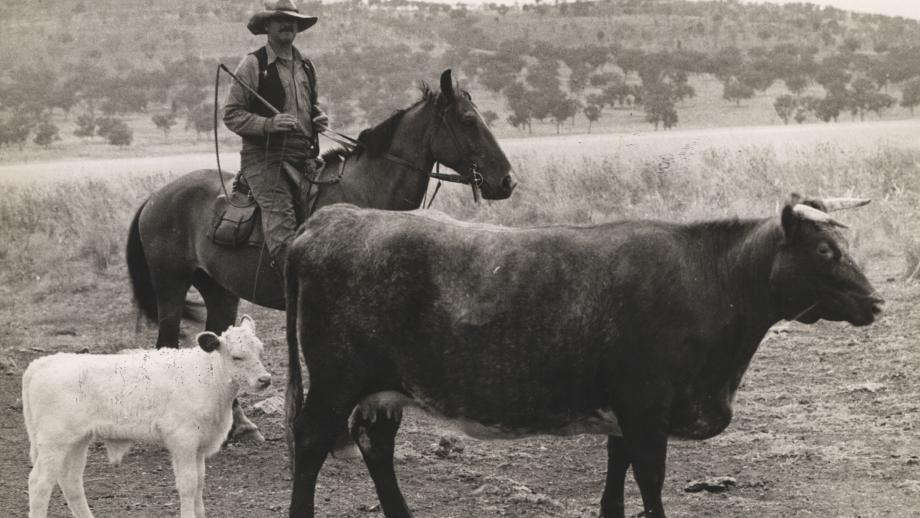

With the Company operating three separate estates centred around Port Stephens, the Peel Valley (Goonoo Goonoo), and the Liverpool Plains (Warrah), it was essential to ensure efficient transport links between the estates, particularly with the Company’s flocks moved to the Peel and Warrah but the fleece shipped from Port Stephens. The Company had relied heavily on bullocks and drays to ship its wool, as well as rations and stores, from the coast to their inland stations. By the late 1830s the Company was experiencing significant expenses in dray repairs and the loss of bullocks, and this prompted Commissioner Phillip Parker King to suggest the use of mules for transportation. Consequently, the Company arranged for 20 mules, two asses and three huasos (muleteers) to be contracted in Chile and travel to Australia. Unfortunately, 11 of the mules died en route but the remaining animals and huasos arrived in Sydney in April 1840, with the men contracted to work for the Company for a year. While one huaso returned to Chile after a year, the remaining two signed contracts to stay for a further three years and delivered rations to Nowendoc, the Mountain Station, until 1853, when they, along with many others, left for the goldfields.

In the early 1850s, as expenditure on wages, decreasing profits, and critical labour shortages combined to make conditions very difficult, it was suggested the Company target Chinese workers and General Superintendent Archibald Blane arranged to recruit 80 Chinese workers on five-year contracts. The initial intention was for most of these men to work as shepherds, however it quickly became apparent that this was not the type of work to which most were suited. Instead, the Chinese were employed improving the road at Hungry Hill, with others working on the dam at Stroud, and the remainder at the garden and vineyard at Tahlee. Assistant General Superintendent Philip Gidley King was particularly enthusiastic about the road party, writing “they have made the road passable to drays as far as they have gone, with much less labour than I had allowed for in my report”. Ultimately many of the Chinese workers left, feeling that they had been misled by their contracts, being paid 12/- per month rather than the 15/- they believed they would receive. Of those that stayed on, some worked as shepherds, others stayed working on the road party, and some bought land at Stroud.

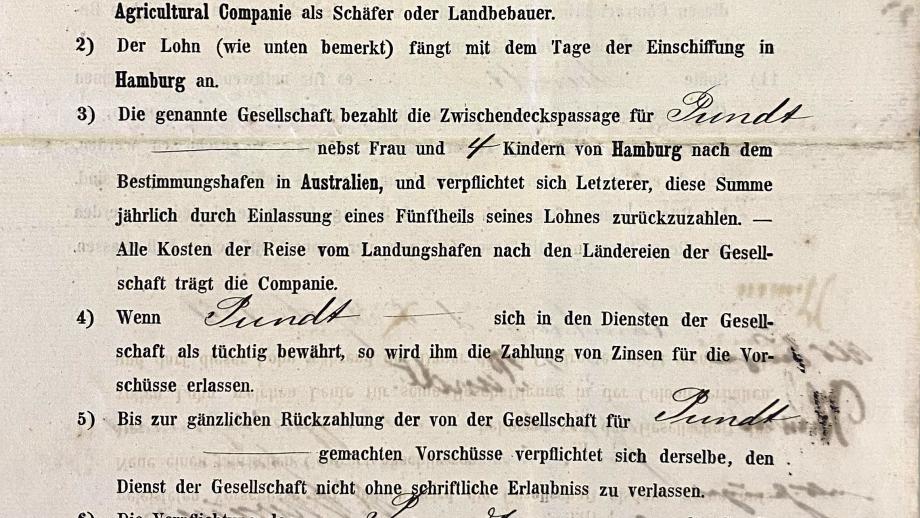

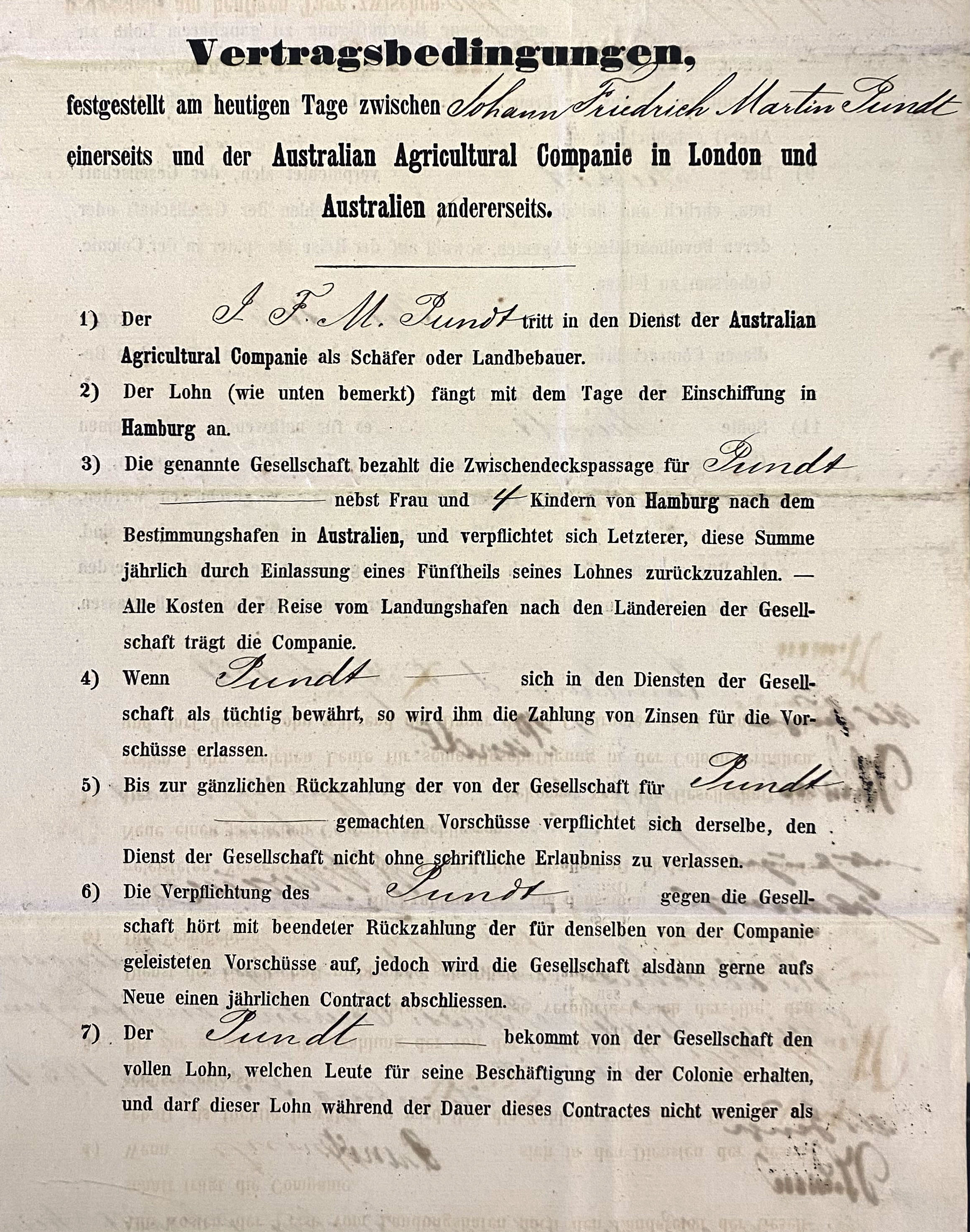

The Company also recruited a number of men from Germany, specifically men who could work as shepherds on the Company’s estates. By the late 1840s the Company was increasingly worried about the condition of the sheep at the Port Stephens Estate, with low birthing rates and high mortality, particularly in comparison to the sheep which had been moved to the Peel Estate, who were thriving. In London in April 1854 the Chairman of the Peel River Land and Mineral Company, Count Paul Strzelecki, suggested the Company send out shepherds from Germany, as well as some additional sheep to add new blood to the flocks. In 1854, five German shepherds accompanied 26 Saxon Merino rams, 26 Saxon Merino ewes, and 10 Mecklenburg Merino ewes from Germany, to be divided between the Australian Agricultural Company and Peel River Land and Mineral Company. In the ensuing months, another 36 shepherds were sent from Germany, along with five miners. While some of the Germans made it successfully to Port Stephens and the Peel, some absconded on their arrival in Australia, with some feeling misled by the agents who recruited them. While some worked as shepherds, a number were instead sent to work on the road to the North Arm Depot at Port Stephens, with others employed as fencers, bullock drivers and sawyers.