The Dalfram Dispute

The Dalfram Dispute was one of the most important campaigns in the history of the Waterside Workers' Federation and was a result of the union’s strong opposition to the Japanese invasion of China.

In September 1931, the Japanese invaded the Chinese province of Manchuria. By 1937, they controlled large sections of the country. The conflict was known as the Second Sino-Japanese War and was a result of Japan’s desire to source more raw materials to fuel its growing economy. The conflict ultimately resulted in the deaths of approximately 15 million Chinese people and widespread destruction of the country’s industrial and agricultural systems.

The Australian response to the conflict was mixed. While the Japanese actions were widely condemned, there was a desire to keep a distance and not become involved in a conflict that did not directly concern us. However, the WWF launched action across Australian ports to attempt to cripple the supply of raw materials to Japan.

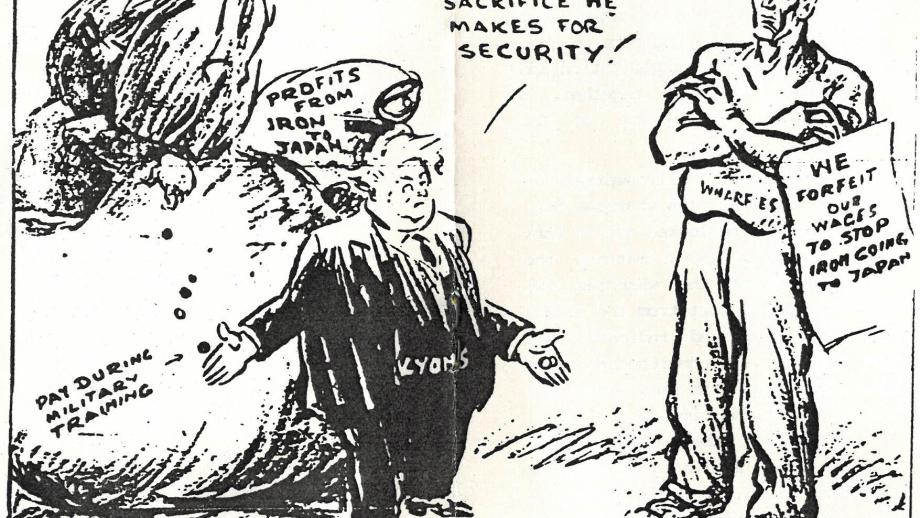

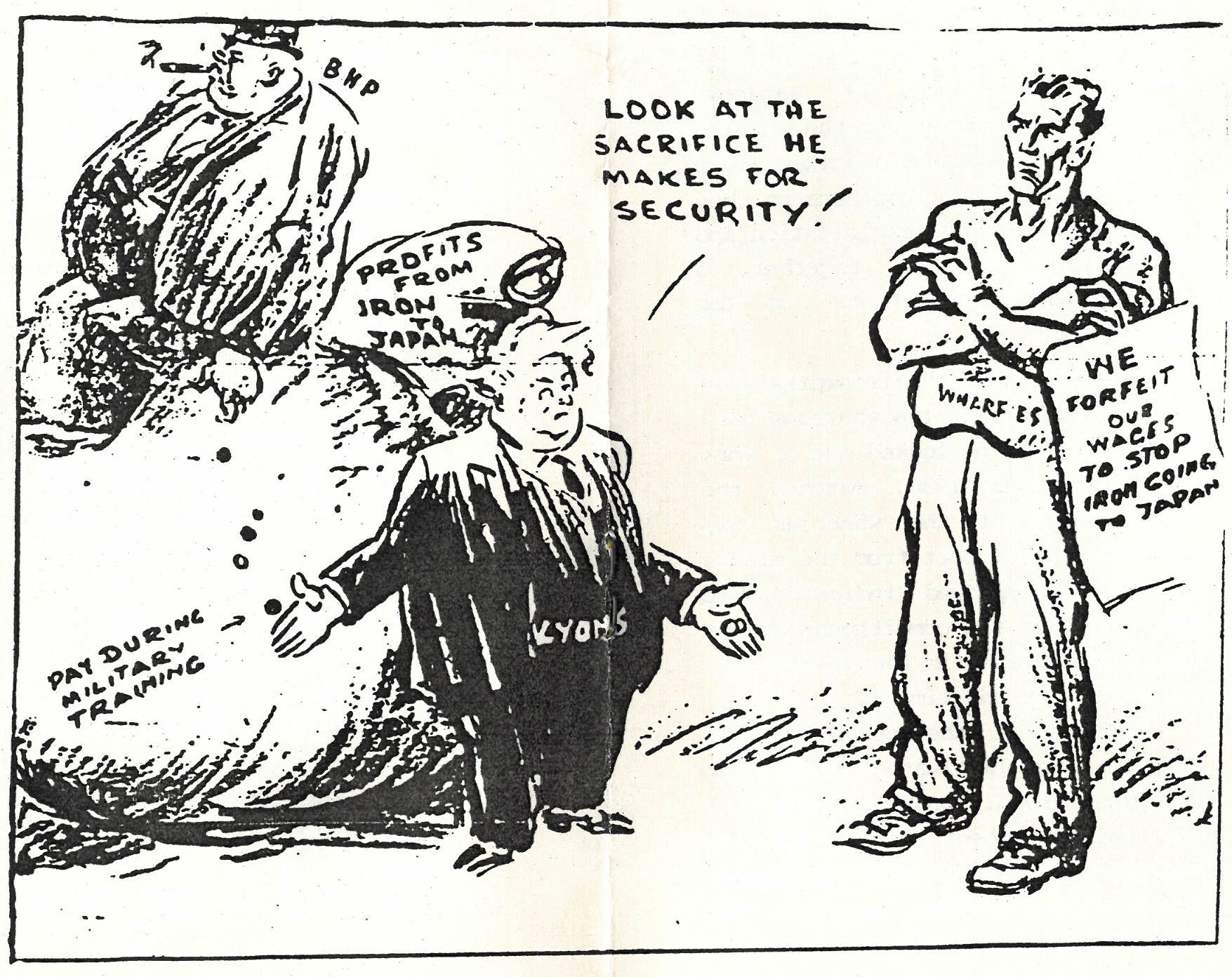

On 12 October 1937 in Fremantle, Western Australia, members of the Fremantle Lumpers’ Union refused to load coal on the Japanese ship Tonan Maru No 1 (McDougall 1977, p. 48). Similar protests occurred in Geelong, Sydney, Melbourne, Adelaide, Hobart and Brisbane. By May 1938, Prime Minister Joseph Lyons threatened to invoke the licensing provisions of the Transport Workers’ Act (Dog Collar Act) against waterside workers if they did not end their embargo. The WWF ended the embargo in response, but this was certainly not the end of the matter.

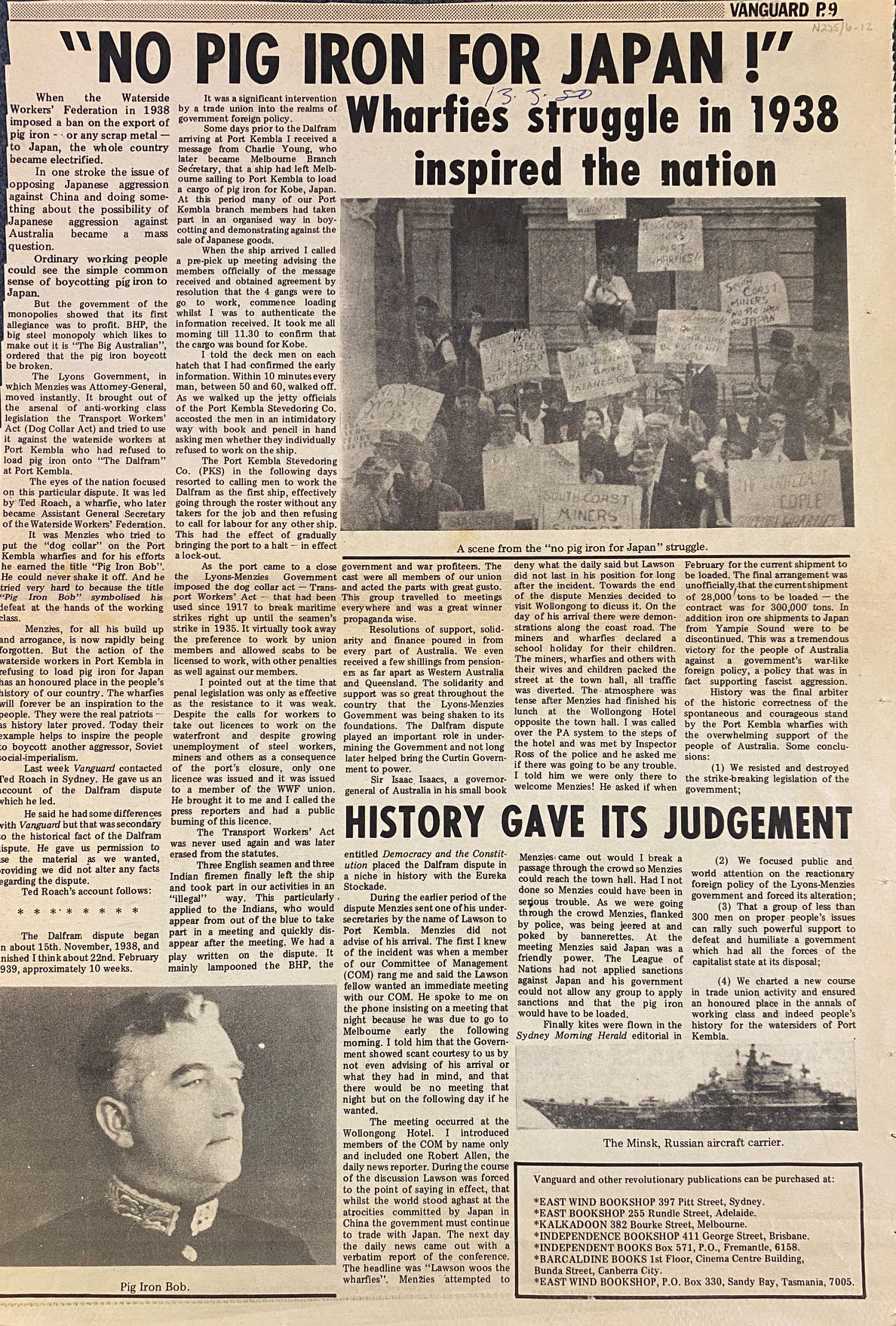

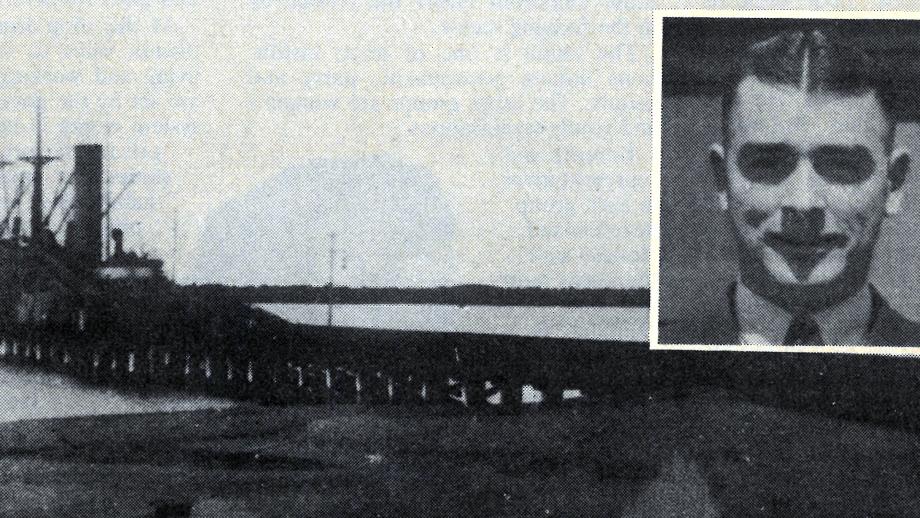

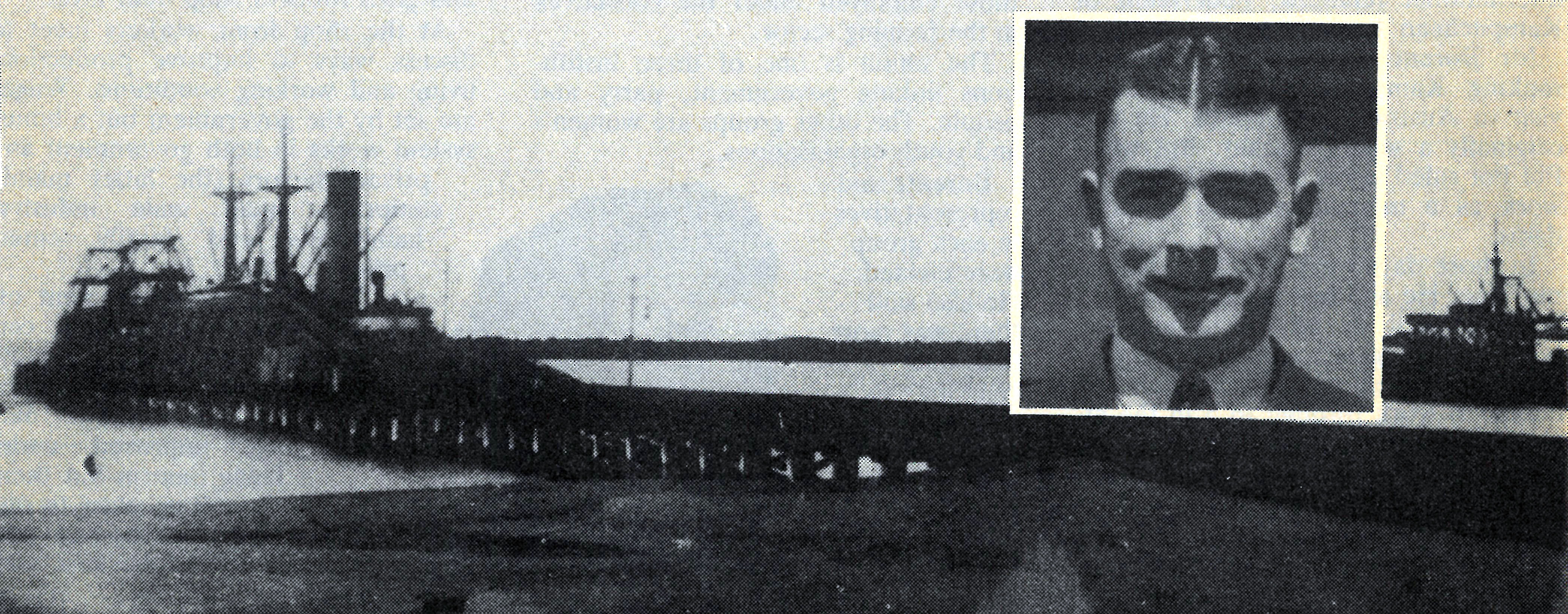

On 15 November 1938, the steamship Dalfram berthed at Port Kembla, New South Wales. It had been contracted by the Japan Steel Works Ltd to ship pig iron to Japan. Ted Roach, Secretary of the Waterside Workers' Federation New South Wales South Coast Branch, addressed the men at the Dalfram’s labour pick up and urged them not to load the iron, reminding them that it would produce weapons to be used against the Chinese, and perhaps also eventually against Australians. The following day, not a single worker put themselves forward to load the ship. The employer’s responded by refusing to pick up labourers for any new ships, sparking an 11-week lock out.

The Port Kembla wharfies were largely supported by the WWF, although early on, Jim Healy sought to quell the dispute by negotiating a settlement with the Menzies Government. However, it became clear that the South Coast Branch was not afraid to break new ground by implementing action at a local level and would not be dictated to by the Committee of Management (Mallory 1999).

The wharfies received wide support from other unions, the Australian Council of Trade Unions, the NSW Trades & Labor Council and Melbourne Trades Hall Council. They argued that the shipment of pig iron to Japan was morally wrong and urged the government to reconsider their position, which they did. Lyons announced an embargo to take effect from July 1939, although the government argued that the embargo was simply necessary to conserve Australian resources. Ironically, this announcement was not well received by some in the ALP, including John Curtin, and the Australian Workers’ Union, who argued that the embargo would create unemployment and harm Australia’s economy (McDougall 1977, p. 52).

On 7 December 1938, the Federal Government made good on their threat and applied the Transport Workers’ Act at Port Kembla, requiring all workers to be licensed. Only one wharfie applied for a license and Ted Roach convinced him to surrender it so it could be publicly burned at Customs House (Mallory 1999). The wharves were subsequently declared black. The union had demonstrated that the government could not count on using the Transport Workers’ Act against them. Later that month, the dispute escalated when BHP laid off 4,000 workers at its Port Kembla Steelworks, arguing this was necessary because of the Dalfram Dispute.

On 11 January 1939, Attorney General Robert Menzies visited Wollongong to attend a combined union committee meeting and attempt to resolve the dispute. The locals were ready for him and he was met by a hostile crowd of approximately 1,000 people. Amongst the crowd was Gwendoline Croft, from the WWF Women’s Committee, who shouted ‘Pig Iron Bob’ at Menzies, thus earning him the enduring nickname.

Following a meeting with the WWF, Menzies gave assurances that the government would review its policy and remove the requirement for workers to be licensed. While workers were loath to accept the government’s word, the standown of thousands of BHP workers was hard for the local community to endure, and later that month, wharfies loaded pig iron under protest. There was also contention about the destination of other shipments loaded in early 1939.

The Dalfram Dispute had far-reaching consequences. It demonstrated that when workers took action as a united collective, the government lost its power and could no longer expect the threat of the Transport Workers’ Act to be an effective tool in quashing industrial action. The dispute also sparked the dissemination of militancy throughout the union’s branches and an increased ability to succeed in industrial actions throughout the 20th century.

References

Mallory, G n.d., The 1938 Pig-Iron Dalfram Dispute and Wharfies Leader Ted Roach, Australian Society for the Study of Labour History, <https://www.labourhistory.org.au/hummer/vol-3-no-2/dalfram-pig-iron/>

McDougall, D 1977, ‘The Australian Labour Movement and the Sino-Japanese War, 1937-1939’, Labour History, No. 33, <https://www.jstor.org/stable/27508280>